Why We Need Public Libraries Now More than Ever

Who needs libraries, anyway? Turns out, we all do.

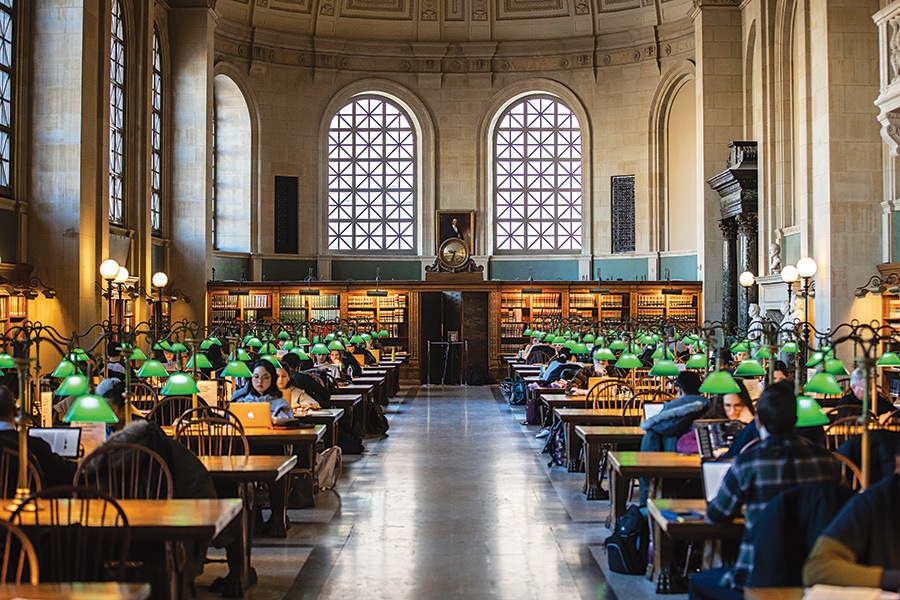

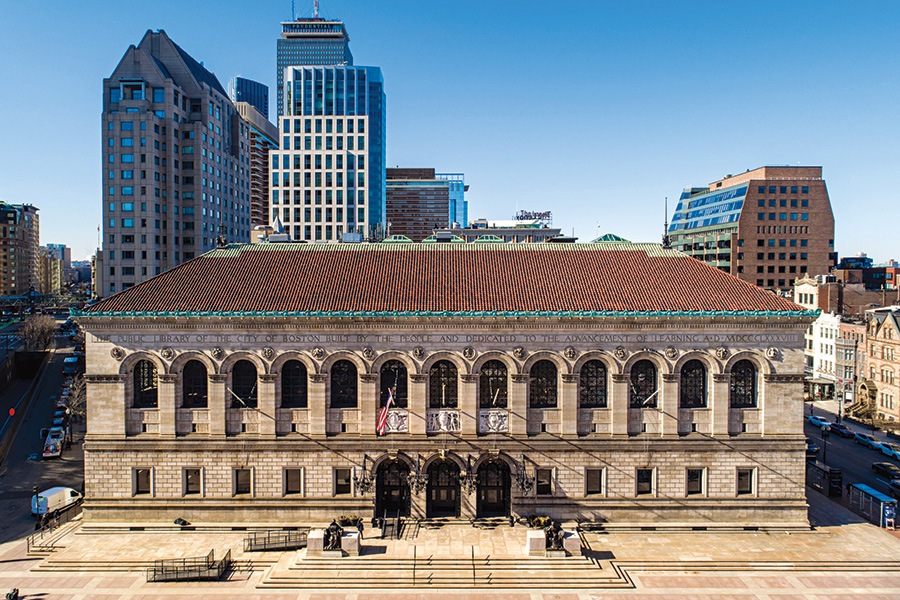

The BPL’s historical Central Library in Copley Square, the crown jewel of the system. / Photo by Aram Boghosian for the Boston Public Library

It’s 10 o’clock on a bright summer morning, and the Boston Public Library—175 years old and more vital and necessary than ever—is up and running, doing all the things that public libraries do, offering all the things that public libraries offer.

On the first floor of the Central Library’s Boylston Street Building, a modern and inviting space built in 1972 and renovated in 2016, people are browsing for books, working on laptops, and sipping macchiatos from the library’s Newsfeed Café, which sits just a few feet from the ground-floor radio studio built and operated by GBH. In gorgeous and historic Bates Hall, on the second floor of the adjoining McKim Building, studious-looking Bostonians are sitting quietly at dozens of orderly reading tables, the same way studious-looking Bostonians have been sitting quietly at orderly reading tables inside Bates Hall for more than a century. Meanwhile, at the library’s two dozen branch locations all over Boston, staffers are gearing up for story hours, tech sessions, reading groups, and all the things that take place daily inside their buildings. And then there’s David Leonard, president of the BPL, who at this particular moment is in a Central Library conference room not far from his office, contemplating an odd question I’ve just lobbed his way.

“If public libraries didn’t exist and we tried to start them today,” I’d asked, “what do you think would happen?” By which I meant: Would the public, not to mention the powers that be, agree with this idea of pooling our money and opening up a bunch of buildings where people can come and “borrow” books, with the simple promise that they’ll bring them back when they’ve finished reading them?

It is, as I’ve noted, kind of a whopper of a query, particularly for 10 o’clock in the morning, but I think it’s a legitimate one. To begin with, there’s the record level of attempted book banning that’s been happening at school and community libraries across the country of late. According to the American Library Association, there were more than 1,200 attempts to censor books and materials at libraries nationwide in 2022, 58 percent of which targeted materials in schools and 41 percent were aimed at public libraries. Though attempts to ban books have increased in recent years, they’ve largely been unsuccessful, especially at public libraries. For its part, the BPL has largely—thankfully—been spared such attempts at community censorship, but the bans writ large don’t exactly inspire faith that everyone everywhere is all in on the idea of public libraries. Beyond that, there’s the very obvious fact that we now live in a digital age, with tiny computers in our pockets at all times that are capable of tracking down whatever information we might desire with just a few taps of our opposable thumbs. Do we still need a building—let alone two dozen of them—with a bunch of heavy, musty books inside? Finally, there’s the business model for all of this—or, should I say, the lack of one. The BPL’s motto, emblazoned on many of its buildings, is “Free to All.” In a private-equity world, “free” isn’t something we do much of, let alone “for all.”

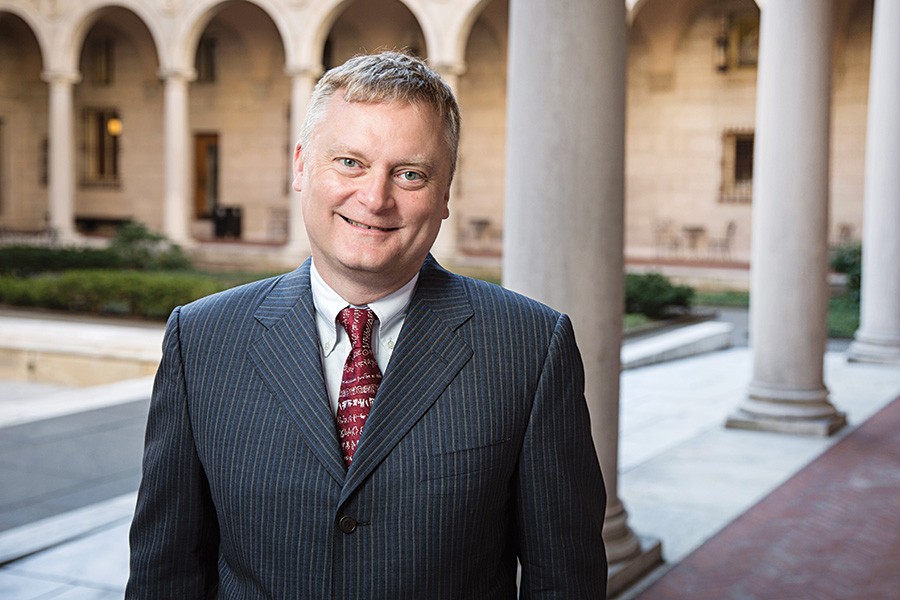

Boston Public Library president David Leonard. / Photo by Aram Boghosian for the Boston Public Library

Leonard, a 56-year-old native of Dublin, Ireland, who’s dressed today in a purple shirt and blue blazer, has a master’s in philosophy from University College Dublin, and he’s working on a doctorate in library information science from Simmons University. So he’s hardly thrown by Big Questions, and he does his best to take mine in stride.

“The quick answer is, I’m so glad we don’t have to [start libraries today], because we have 175 years of delivering value,” he says. He pauses for a moment and then leans in a little more to what I’m trying to get at.

“I think the deeper philosophical question in there is, what kind of society do we want to live in? Where do we want public discourse to exist? How do we want to control information and knowledge? I think if the library didn’t exist, we would need it,” he says, then adds, “But in today’s particular version of Western democratic capitalism, it is very difficult to envision how that would come about.”

I should take a moment here to acknowledge that not only was my question for Leonard a little odd, but so is the whole piece you are (I hope) about to read. An entire magazine feature on…the library? What next, a treatise on the intricacies of the Boston sewer system? A takeout on bridge fortification? I get it. The library isn’t new—Zachary Taylor was incoming president of the United States when the BPL was established, and that was so long ago most of us couldn’t possibly distinguish him from John Tyler. (You’ll get no help here.) The library isn’t particularly mysterious—your average Boston seven-year-old has a pretty good handle on how the whole thing works. The library isn’t even in crisis. On the contrary, no city in America loves its libraries more than Boston does, in part because Boston is one of the great library cities. Last year, the BPL had more than 2.1 million visits and loaned out some 660,000 print books and 3.8 million digital items. It’s one reason that politicians keep sustaining the BPL with plenty of money. (Its annual operating budget is just under $50 million.)

And yet, I somehow feel compelled to not only write about libraries but to ask you to ride shotgun while I explore and—spoiler alert—sort of gaze in wonder at what they do. Because where else, I ask, can you not only borrow a book or get an answer to a question that plagues you but also get help with your taxes? Or take a cooking class? Or meet up with people who like Legos? Or get married?

I will admit to a personal bias here. I’m a writer, first of all, one with a book coming out next year, and so a public institution that’s all about reading is hardly one I’m going to quibble with. More important, I come from a library family. My mother spent decades as the children’s librarian in the small town where I grew up. My mother-in-law worked in a library, and my wife’s three siblings all became librarians. My people? We’re library people.

Still, I think there’s something deeper going on here, too. Because the more I’ve thought about public libraries in general, and the BPL in particular, the more I’m convinced they have something to tell us about where we’ve been, where we are, and where we need to go.

There’s never a dull moment at the BPL. Interns conduct inventory at the Central Library. / Photo by Angela Rowlings/ MediaNewsGroup/Boston Herald

“Hello. Are you here for the English class?” Jenna asks.

“Yes,” the young woman says.

“You’re in the right place,” Jenna warmly assures her before the woman walks into the room.

One recent morning, I was at the BPL’s West End branch—a no-frills building several blocks away from Mass General—sitting in on one of the English-as-a-second-language (ESL) classes that this branch, like most BPL branches, offers weekly. There are a dozen people here, most in their twenties and thirties, and our instructor is a young woman named Jenna.

Jenna tells the class—students who’ve reached the intermediate level of English—that she’s not going to do any grammar instruction today. Instead, she’s going to lead them in an exercise that’s more interactive.

“The topic is going to be called ‘Desert Island,’” Jenna says. She asks each student to think about five things they might bring with them if they were stranded on a desert island for a year, and then she passes out a worksheet.

“Okay, a couple of notes,” she says after a few minutes of peering over people’s shoulders. “First, the singular of knife is with an ‘f.’ It’s such a strange word. K-N-I-F-E. The plural is the form with the ‘v.’ I saw a couple of people put K-N-I-V-E.”

“Another note: I saw a couple of people put the wrong word after ‘first aid.’ We do not say ‘first-aid box,’” she explains. “The more common way to say it is ‘first-aid kit.’” The class nods their heads, and I thank God that English is my first language.

Books—or, more broadly, literacy—have traditionally been the backbone of what the BPL does, and that’s still the case. The library’s collection holds more than 23 million items, which makes it the third-largest library in the United States, behind only the Library of Congress and the New York Public Library. That collection holds everything from the latest bestsellers by J.D. Robb and Prince Harry to rare medieval manuscripts dating to the 14th century. Beyond just lending books, though, the BPL does much to support reading in general, from book discussion groups and children’s story hours to live conversations with prominent authors.

Still, over the past couple of decades, like many public libraries across the country, the BPL has extended its reach beyond just literacy to meeting community needs more broadly. “Personally, I think books are sort of like the baseline for libraries,” says Celia Contelmo, who runs the BPL’s Grove Hall branch in Dorchester. “What we do here at this branch is less about books and more about community and the other needs that people have.”

Grove Hall serves a largely Hispanic neighborhood, and as I sit inside the branch one afternoon with Contelmo and Priscilla Foley, the BPL’s director of neighborhood services, I ask for some examples. Contelmo, a soft-spoken young woman with a nose ring and an array of cool tattoos, brightens.

“I could talk about that for hours,” she says.

She walks me through the impressive menagerie of what happens here at Grove Hall: ESL classes. Sewing workshops for teens. Mixers for seniors. Family movie nights. Painting and creative-writing workshops held in conjunction with MassArt and GrubStreet. Health information sessions held in conjunction with the Boston Public Health Commission. An annual summer tea party organized by the branch’s children’s librarian, as well as an annual ice cream social. The list goes on. And those are just the formal programs. Every day, Contelmo says, people come in needing assistance with something—from looking for a new job to setting up a new phone—and the library staff spring into action. Tech help, in particular, is a common request. During COVID, Grove Hall and other branches boosted their WiFi networks so that they were available outside the building, and that’s now become an essential service in many Boston neighborhoods.

“There are times when I’m showing up at branches at 7 o’clock in the morning, and there are people lined up on the steps using WiFi,” Foley says. “And I’m like, I’m so happy you’re here.”

If traditionalists grumble that libraries should stick to lending books, David Leonard and every person I spoke to at the BPL had a different take. They see programming and services as natural extensions of the reference and research function libraries have always offered. “You have a question, you have a quest, you have a piece of information you’re seeking,” Leonard says. Once upon a time, such quests might have been straightforward—Excuse me, I’d like to learn more about Zachary Taylor—but today, they’re broader and perhaps more urgent, at least if you’re willing to listen.

“People who are housing-insecure come to the library, and their information request, whether they articulate it or not, is, ‘I need to get stable in my life, and maybe I need access to resources,’” Leonard says. To handle such requests, the BPL has, in recent years, beefed up its own resources, now employing a social worker and a health librarian, as well as a new youth-employment counselor whose sole function is to help young people find work.

For many of the librarians, giving the community what it needs—free of charge—is at the core of their passion for the job. “You get a pretty good feel for the demographics of the neighborhood and their interests,” Contelmo says. “We try to program around that. It’s not my interest, but the interest of the community.”

Then she confesses something that, in libraries of yore, might have gotten her shushed by a colleague but no longer feels so unusual or verboten. “I’m not a big reader,” Contelmo admits. “And so I get it when people come in here, and they’re just not into books. But the library offers so much more.”

Ironically, for all of the scheduled programming it offers, the BPL has discovered one of the biggest services it provides is simply its space—giving people a place to be. For free. “I think traditionally we may have thought, Well, we have these great buildings, and some of them are really beautiful. But they were the containers within which other things happened,” Leonard says. “Whereas in today’s world, post-COVID, the space itself is part of the service.”

To walk around the Central Library or any BPL branch is to see people engaged in a variety of activities. Yes, some are doing traditional library things—browsing the latest bestsellers or searching for something to read with their kids. But others are working (Leonard calls the library the original coworking space) or studying or collaborating on a group project. Still others are there simply as an escape from the heat or cold. On the day I’m at the West End branch, I see two people sitting in chairs with their eyes closed. Are they homeless? Dealing with addiction issues? I have no way of knowing, but they’re not disturbing anyone, and they’re left alone.

“If you appear to be asleep, we will interrupt you to do a wellness check,” reads a sign I see at the Central Library. It’s an elegant message that communicates two things at once: We want to make sure you’re well, and we’ll try to help you if you’re not. But also: You have as much right to be here as anyone else. This space is for everybody.

Ironically, for all of the scheduled programming it offers, the BPL has discovered one of the biggest services it provides is simply its space—giving people a place to be. For free.

Photo by Aram Boghosian for the Boston Public Library

The cliché about libraries is that they’re serene spaces in which you’re not supposed to make a sound—which is why, I guess, I find it kind of awesome and hilarious that the Boston Public Library owes its existence, in part, to a ventriloquist.

The ventriloquist in question was Frenchman Nicolas Marie Alexandre Vattemare, who became world-famous in the first half of the 19th century for his ventriloquism skills, earning a small fortune as he performed for audiences (including royalty) all over Europe. As it happened, Vattemare—who, as a young man, trained as a surgeon but was said to have been refused a diploma after making the med school cadavers “speak”—wasn’t just a crack performer, but a sophisticate who hung around with other artists and writers of the age and who in retirement poured much of his energy and money into encouraging and arranging cultural exchanges between Europe and the United States. In the 1840s, Vattemare proposed unifying all of Boston’s “social libraries”—private book collections that people had to pay to access. He befriended Boston Mayor Josiah Quincy Jr., who became an advocate for a truly public library. In 1848, by an act of the General Court of Massachusetts, the BPL was founded, and six years later, with 16,000 volumes in its collection, the first library opened in a former schoolhouse on Mason Street.

Vattemare and Quincy were two key figures in the BPL’s founding and development, but there were others: Edward Everett and George Ticknor (the first two presidents of the board of trustees); financier Joshua Bates (whose $100,000 donation eventually got him the reading room named in his honor); architect Charles Kirk Kirby, who designed a new building that opened in 1858; and architect Charles Follen McKim, who in 1895 completed the Back Bay structure that still stands and bears his name to this day.

Of course, as important as such people were in establishing the library, equally important was the era in which they lived. Not to go all 10th-grade U.S. history on you, but the BPL was founded in what historians refer to as America’s age of “national expansion and reform.” That era’s two hallmarks: a growing nation’s push westward (a, uh, complicated subject, to say the least), and the presence of numerous “reform” movements, most of which had at their core the notion that human beings—and society in general—could be improved. It was an age marked by religious revivals, as well as by the birth of the abolitionist and women’s movements and America’s deepening commitment to public education. Fitting neatly alongside all of those noble undertakings was this idea of libraries, not just for the well-off and socially connected, but for the general public, who’d have access to them for no cost at all. The first free public library in America opened in Peterborough, New Hampshire, in 1833. The Boston Public Library was the second. Today, there are more than 9,000 public libraries in the U.S.

Now, it’s worth pointing out that while public libraries in general—and the BPL in particular—are the products of a certain kind of civic idealism, libraries have sometimes gotten caught up in, and occasionally been brought down by, social trends that are less worth emulating. Locally, the most notable example was the censorious period that ran from the late 1800s to the 1960s—the “banned in Boston” era in which scores of books, plays, films, and songs were deemed objectionable and either officially banned by Boston city officials or effectively banned by private groups such as the Watch and Ward Society. (A quick refresher on some of the works deemed illicit in our fair city: Whitman’s Leaves of Grass; Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises; Dreiser’s An American Tragedy; and Odets’s Waiting for Lefty.) I didn’t find any evidence that the BPL led the charge on such censorship, but I also didn’t come across any moments when it took heroic stands against what was happening, either. In many cases, it seems, the BPL simply put the banned books in locked rooms called “the Inferno” so that the public wouldn’t be “corrupted” by them.

Vattemare was long dead by then, but the idealist in me hopes he would have spoken out against what was happening. Even if no one saw his lips move.

A public library is, depending on your choice of metaphor, either an act of faith or a bet. The proposition: If we can make information and ideas—in short, human knowledge—easily accessible to average people, then they’re not only likely to lead richer and more productive lives, but they are also more likely to contribute to making the overall community richer and more productive.

As gambles go, it’s a pretty smart—and safe—one. It’s certainly no accident that as education levels and access to information have risen over the past century, so has our standard of living. What’s more, giving people access to knowledge is the best way to create even more knowledge. Every breakthrough someone makes in, say, science and technology is built upon a breakthrough that someone else made before them. Mark Zuckerberg couldn’t have created Facebook in his Harvard dorm room if a handful of computer scientists decades earlier hadn’t created the Internet, and those computer scientists couldn’t have done that without various engineers first creating the modern computer, and those engineers couldn’t have done that without Thomas Edison and others electrifying the world, and Edison et al. couldn’t have done that without…well, you get the idea. Back and back it goes. Human knowledge is a building that’s continually under construction, each generation adding a layer of bricks on top of what was already there. And, of course, it’s inside libraries—big public ones like the BPL, impressive research ones like those at Harvard and MIT, and even private ones like the Boston Athenaeum—where many of those bricks can be found.

Tech Central at the Boston Public Library. / Courtesy photo

On the same day that I chat with Leonard, I’m invited on a quick tour of the Central Library by its manager, Anna Fahey-Flynn, and Lisa Pollack, the BPL’s chief of communications. The first place they take me is the library’s Special Collections Department, a vast and much-heralded treasure trove of rare and valuable books, manuscripts, and pieces of art. Among them: John Adams’s library (3,000 volumes assembled by the second U.S. president); a copy of Shakespeare’s First Folio; four original printings of the Declaration of Independence; a complete run of the abolitionist newspaper The Liberator; and Robert McCloskey’s sketchbooks, including drawings for Make Way for Ducklings.

The department recently underwent a nearly $16 million renovation that improved both its public spaces and its storage areas (including 7 miles of shelving). As I stand in the sleek new lobby, peering through a thick glass wall to where some of the materials are stored in a climate-controlled environment, I feel a little like I’m on the set of a caper movie, with Tom Cruise about to descend from the ceiling. And apparently, I’m not the only one thinking Hollywood. Pollack explains that when the department was being renovated, they had to move a quarter-million volumes out of the library in what she describes as “James Bond conditions”; security accompanied the books every step of the way, and the books were stored—“I’m not making this up,” Pollack tells me—at an undisclosed location in upstate New York.

Our tour continues, with Fahey-Flynn and Pollack leading me up and down elevators and through the corridors that comprise the Central Library’s innards. If the Boylston Street Building is contemporary and bright and the McKim Building is impressive and historic, this part of the library is drab and claustrophobic, like an insurance company office last updated in 1969.

Suddenly, we pass through a door and pop out into what was once another large reading room inside the McKim Building—a space with big, gorgeous windows that’s now used only for storage. Inside the room are about a dozen 6-foot-high metal carts, on which have been stacked hundreds of scrolls wrapped in plastic.

“Blueprints,” Fahey-Flynn explains. Neither she nor Pollack are sure where they’re from, but as we pass through the room, I look at some of the tags attached to the plastic. On one: St. James Church, New York, New York. Another: St. Paul’s Cathedral, Detroit, Michigan. Both are from the early part of the last century.

A production assistant digitizes stereoviews from the late 1800s to 1920s. / Courtesy photo

A major challenge of running a library like the BPL is what to do with all the stuff—books, drawings, photos, audio recordings, videotapes, microfilm; you name it—that’s been created by people in the past, and that amounts to a record of human activity. A sizable chunk of the BPL’s overall collection is old government records the organization is required to hold onto as part of its role as both a state and federal depository library. As a service, this is great—we have access to the official accounting of what came before us—but it creates the compounding problem of where the hell to put everything. The majority of what the BPL owns is housed in the Central Library, as well as several million items that are stored in an offsite archives building, an old electrical warehouse in Roxbury. But even that, I’m told, is now bursting at the seams.

For most of their existence, libraries had a near monopoly on this warehousing of human knowledge, but in the age of the Internet, that’s changed. When we want information now, most of us simply Google and click, then have served up to us words and data stored on millions of computers around the world. (The indexed World Wide Web alone, a sliver of the Internet, contains nearly 70 billion pages.)

The digitization of the world has, not surprisingly, changed what libraries do in significant ways. Last year, the number of e-books the Boston Public Library lent out, for example, exceeded the number of physical books it circulated by more than five to one. Meanwhile, the library is working to digitize much of its own holdings so they can be viewed by people around the world. And then there are those patrons who simply use their branch library for the WiFi.

If you’re wondering whether all of this has the potential to make public libraries obsolete, or merely reduce them to a bunch of routers and computer terminals, the short answer is: Let’s hope not. The amount of information we can get online—quickly!—is beyond measure, but there are, as we all discuss constantly now, questions about the quality of that information.

“Ah, right!” David Leonard says when I raise this issue with him. “We might be the accurate repository of information, honestly.” Leonard is hardly a Luddite—he spent many years working in the tech business and originally joined the BPL as its Chief Technology Officer—but he makes an important point. While not everything in the library is 100 percent accurate, for sure, there is at least more curation happening than on the Internet. In the early days of COVID, BPL librarians put together a set of resources, backed by academic studies, that tried to give people the most accurate, up-to-date information possible about the virus. One can assume that injecting disinfectant into yourself was not on the list.

The other issue that arises with the Internet is depth. The web may have billions of pages, but when was the last time you went past page one of Google search results? Or got out your credit card to pay for information behind a paywall? “When you Google, the majority of stuff you’re getting is the free stuff,” Fahey-Flynn says. “We put a lot of resources into buying the stuff behind the paywall. And it can be frustrating making sure people know that we actually have those things.”

If the BPL struggles to make the outside world aware of its vast resources, in some ways, it faces the same struggle internally—understanding for itself everything that it has. For the final part of our tour, Fahey-Flynn and Pollack lead me into “the stacks,” multiple floors inside the Central Library with row upon row, shelf upon shelf, of books. The library has commenced gaining “intellectual control,” as Fahey-Flynn puts it, of everything in its collection, but it’s not there yet.

“I have been capital ‘L’ lost in these stacks,” Pollack says as we walk between some shelves that look identical to the shelves we saw on a different part of the floor—or maybe it was the floor beneath us? There’s a vastness to this that’s daunting and breathtaking and miraculous all at once—tens of thousands of books written by tens of thousands of authors over hundreds of years. As we’re walking, I ask if we can pull one off the shelf just to see what it is.

Pollack halts and grabs a random tome. She sighs a little as she touches it. “They’ve all been cleaned—or cleaned as much as they could,” she says. “These books were

really dirty.”

I ask what volume she’s holding. She flips it open and tells me it appears to be in German. “It’s from 1901,” she says. Inside, it has tables and charts and statistics—about what, exactly, is unclear. As we move on, I wonder if it was an inconsequential book or a crucial brick of human knowledge upon which other crucial bricks have been stacked.

Either way, here it is at the library—forgotten, perhaps, but not gone.

Grove Hall library patrons take advantage of hte branch’s many resources. / Courtesy photo

On my final visit to the library, I sit in on another program that the BPL offers for the community: a creative-writing workshop that’s being held on the lower level of the Boylston Street Building. In the room are a dozen people, ranging in age from twentysomething to retiree.

This is the first session of a multiweek class, and so to kick things off, the instructor, a BPL employee named Jordan, goes around the room asking people to share what they like to read and what they’re hoping to get out of the course. The responses and favorite genres are predictably varied: One person is a fan of gay romance novels with a dash of sci-fi. Another loves historical fiction. Another started keeping a journal while she was stuck at home during COVID with her five-year-old, and now she’s interested in memoir. Finally, we get to one of the older members of the group, Valerie, who shares that she started doing genealogy research during COVID and learned about an ancestor who was born in England in 1547. “I became really fascinated with this character, and he is living inside my head,” she says. “I have to do something with it. I feel a compulsion to do it, but I have no idea how to do this. But I have got to get something outside of me about this man.”

Human knowledge is filled with facts and figures—statistical charts annotated in German, for instance—but it’s more than that. We mostly make sense of the world through characters and narratives, through stories. And what is the library but the place where we store the stories we tell ourselves about ourselves? Some of those stories are factual; others are make-believe. Some tales are meant to entertain us, others to inspire us, instruct us, or challenge us. But what makes them work, when they work, is that we somehow recognize ourselves in them.

At the heart of our divide in America today is a disagreement, more pitched than it’s been in a while, about some of those stories. Which narratives are true, and which ones aren’t? Sometimes, the difference is easy to see: The 2020 presidential election wasn’t stolen, no matter how much Donald Trump spins a fantastic tale that it was. But other times, it’s harder to find clarity. Was the United States founded by an idealistic group of people who believed in freedom and democracy and were willing to put their lives on the line for it? Or was it created by a slave-holding gentry who only cared about their economic interests? Could both be true? Or neither?

A disagreement about narrative is also what underpins our clashes over books. For those of us who believe libraries should proudly display books about Black history or gay or trans people, the push is for one of increasing inclusivity—everybody is part of the story. To those who want certain books banned, the narrative is one that never really has—and in their mind never should—include certain people.

Leonard—and the other librarians I spoke to—acknowledge that the BPL has been lucky in that it’s had very few challenges about the books and programs it offers, though there have been some. “We have had people who don’t really agree with some of our programming,” Leonard says, “whether it’s Pride month–related or related to racial equity. So we do have some of that.”

When it happens, Leonard falls back on a standard response. “I try to remind people that there’s no mandatory reading list that comes with a BPL card. You can choose which things are relevant to your values or your interests. You don’t have to come to specific programming if it’s not for you. But it is very important that we have offerings that respond in particular to the needs of those whose voices are not always uplifted or recognized in our society.”

“‘Free to All’ encapsulates what we’re all about,” he continues. “And the ‘all’ part is as important as the ‘free’ part in that phrase. It really has to be everybody.”

The genius of public libraries is that they were created by citizens, and their only agenda is to collect what humans know—and perhaps try to be helpful.

Let’s finish where we started. If public libraries didn’t exist, could we start them today?

Leonard was hesitant to say that we could, and I share that reluctant skepticism. Not because of attempted book bans or the Internet, but because we don’t do very many things these days with the sole purpose of serving the public good. One-hundred-and-seventy-five years ago, we were in the middle of an age of expansion and reform; today, we’re in an age of many things, but surely one of them is hyper-capitalism. We create what makes money.

There have been benefits from that. Wealth has been generated, and technological progress has been made. At the same time, we have economic inequality not seen in a century and a focus on self that I have to wonder if we’ve ever seen. Maybe the most insidious thing about our era of money is that it has encouraged us to view ourselves only as consumers, never as citizens. Being a consumer is easy and fun—we want what we want, and if we don’t get it in one place, we walk down the street and get it somewhere else. Being a citizen is a little harder. Yes, you have rights, but no more than anyone else. You have no choice but to think about other people.

The genius of public libraries is that they were created by citizens for citizens, and their only agenda is to collect what humans know—and perhaps try to be helpful.

Could we build them now? Maybe it doesn’t matter, because we already have them. Our role at the moment, as David Leonard reminds me, is straightforward: “We must not squander this.”

I mentioned my mother at the beginning of this odd story. She’s retired now, but she’s healthy and active and still very much a library user. Occasionally, when I’m out and about with her, she’ll be approached by someone who recognizes her. She’s always warm and gracious and chatty in reply, and afterward, when I ask who that was, she often says the same thing.

“Oh, he used to come to story hour at the library,” she’ll tell me, and that’s all I need to hear.

First published in the print edition of the November 2023 issue with the headline, “Who Needs Libraries, Anyway?”