Study: More People Are Obese Than Underweight

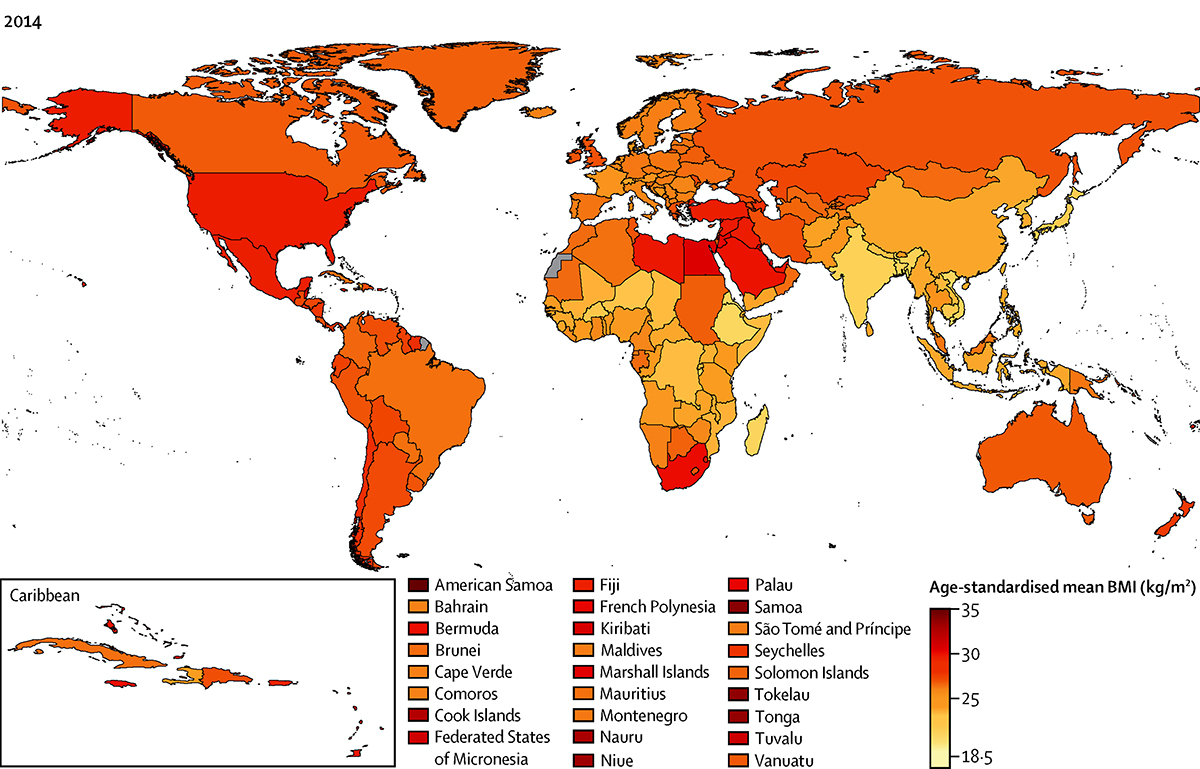

A map showing mean BMIs in 2014. Graphic courtesy of the Lancet

Late last week, the Lancet published a study with a stirring finding: Obese people now outnumber underweight people worldwide.

The researchers found that as of 2014, 10.8 percent of men and 14.9 percent of women worldwide were obese—defined as having a body mass index (BMI) of 30 or higher—while 8.8 percent of men and 9.7 percent of women were underweight. Another 2.3 percent of the world’s men were considered severely obese, compared to 5 percent of women, while .64 percent of men and 1.6 percent of women were morbidly obese.

According to the massive research cohort that completed the analysis, that means obesity may affect at least 18 percent of men and 21 percent of women by 2025. That’s roughly one in every five people, globally.

Of course, being underweight is also a serious health issue, often associated with malnutrition and inhibited development. The analysis is not comparing obese people to “thin” people, as some headlines suggest, but rather comparing rates of two epidemics.

Indeed, Caroline Apovian, a Boston University School of Medicine professor of medicine and pediatrics, says the study, significant for its size and scope, is most striking for showing the overlap between polar opposite weight problems.

That’s demonstrated nowhere better than Asia. The analysis showed that China‚ not the United States, has the highest number of obese individuals in the world—but it also has the second-highest number of underweight citizens. On the flip side, India is home to the most underweight people in the world, and is also third in obesity prevalence. That, Apovian says, illustrates a strange dichotomy.

“Food insecurity may be feeding the obesity rate,” she says. “Initially, these babies and children may have failure to thrive and [be] underweight because of poverty. As they grow older, they’re getting food, but that food is devoid of nutrients because [it] is processed, cheap food.”

Apovian credits that phenomenon to, among other things, sugar-sweetened beverages, processed foods, and an industrial food system that prioritizes efficiency and profitability over nutrition. She says the study reveals a grave need for better social and governmental food policy, and for a large-scale reevaluation of what we eat.

“Yes, we’re feeding all the billions of people on this planet, but we’re feeding them calories without nutrients,” Apovian says. “The big takeaway to me is that, somehow, even though we still have malnutrition, we are able to feed people enough so that they’re becoming obese.”