What the Powerball Craze Says About Us

Photo by tbat54 on Flickr

Photo by tbat54 on Flickr

Last night my husband came home with a Powerball ticket. He’s an economist, so he gets the math. Surely he knew that the chances of winning the $550 million jackpot were 1 in 175,223,510. (Or, as The New York Times ingeniously put it: “The odds of picking the winning numbers in Wednesday’s drawing were longer than the odds of picking an American man completely at random and having him happen to be Alan Alda.”)

But he bought his ticket anyway, hoping to pick the Powerball’s winning numbers. He showed his ticket off as he walked through the door, clearly caught up in the national frenzy that had people who aren’t regular lottery players joining in with the regulars. Twitter lit up with hopeful, funny tweets about what people were going to do with their winnings. A quick anthropological study would suggest that most people in America hate their jobs; not going to work anymore topped most of the bucket lists. Many promised they’d give a chunk of their winnings to the poor. Some said they’d travel. Underlying all those plans and dreams, no matter how playful, was a collective craving, a wish for life to be different than it is.

I remember as a kid marveling about someone winning the lottery and my father saying, “That’s the worst thing that could happen to a person.” His take was that once you’re handed everything, the whole purpose of life evaporates. But even more insidious than winning hundreds of millions overnight might well be spending your whole life dreaming that you will.

In a similar light, on Wednesday Natasha Lennard at Salon wrote about Powerball’s dark side. The day-to-day experience of the lottery is a far cry from the ebullient craze that had people like my husband buying tickets yesterday. Lennard writes:

“A PBS report earlier this year showed that, for America’s very poorest, the lottery is a heavy expenditure: Households that earn at most $13,000 a year spend 9 percent of their money on lottery tickets.”

The article goes on to say that the problem with lotteries is that they exploit poor people’s desire to escape their situations:

“A 2008 study by Carnegie Mellon’s Tepper School of Business, … aligning with national statistics, found that people who felt poor were found to buy double the number of lottery tickets.”

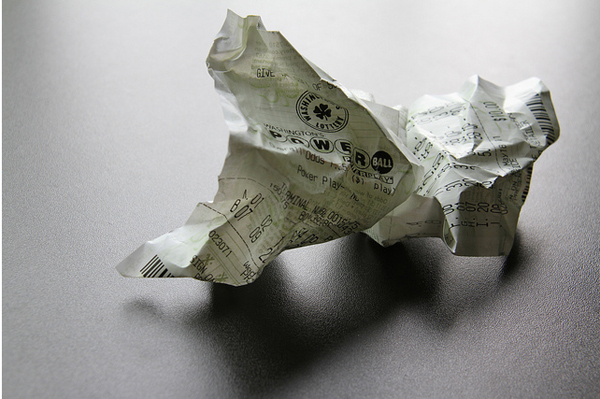

I see these folks every day at the corner store. The clerks know their names and favorite numbers by heart, punching them in as they take their cash. Sometimes they buy the scratch-off cards and when they don’t win, they leave them, along with their hopes and dreams, on the linoleum floor. I know as I watch them that they’ll be back the next day.