Minding the Gap

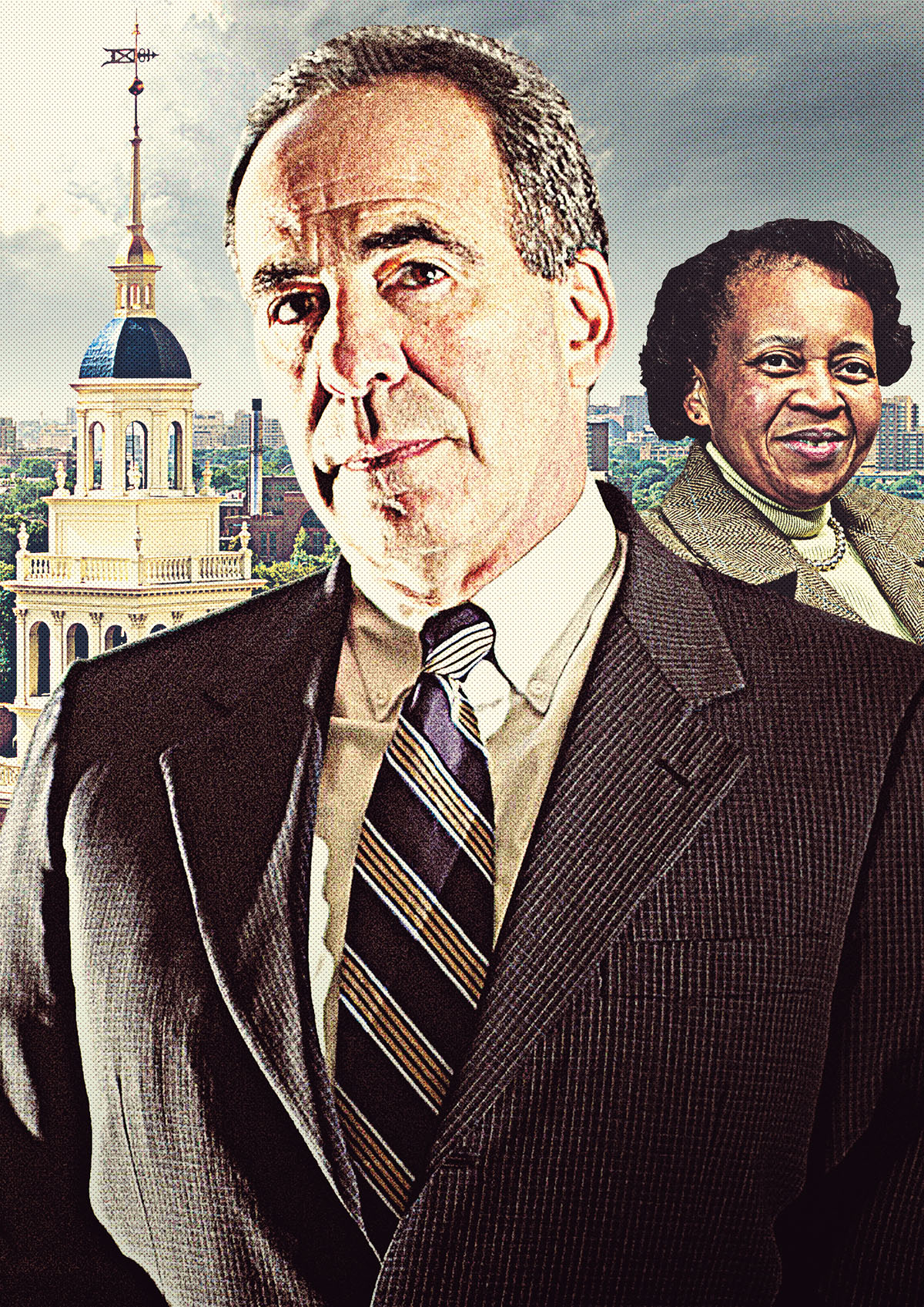

Illustration by Sean McCabe

On a Tuesday night in March, Jeffrey Young stepped into the center of a bright, orange-walled room in the West Cambridge Youth Center. The city’s new superintendent of schools, he stood surrounded by a dozen tables filled with chattering members of the parent-teacher councils from Cambridge’s 12 public elementary schools. The schools currently run kindergarten through eighth grade, and Young had called the meeting to solicit the councils’ input on his plan to create a middle school.

Dressed in khakis, a blazer, and an open-collar white shirt, Young began by outlining the evening’s agenda. “At 7:15, that’s when we’re going to do the great experiment,” he said in his deep, nasally voice, enunciating as though he’d memorized the words. He explained they would move from 12 tables to six, with at least one representative from each school at each table. “The idea here is a kind of cross-pollination,” he said. “We want to be sure that people have the opportunity to engage in close discussion with members of the community who are not part of your regular circle.”

The racial subtext was rich. A quick scan of the room showed mostly white faces at some tables, faces of color at others — they were segregated, not unlike the schools themselves. For years, the number-one issue in the Cambridge system — where nearly 65 percent of the students are minorities, despite a citywide population that is about 70 percent white — has been the achievement gap. Cambridge spends upward of $25,000 per student annually, more than any other municipality in the state, but the system’s MCAS scores trail state averages, with minority students lagging especially far behind their white peers in the district.

Now Young stood before the assembled Cantabrigians as the man charged with providing answers. He stood before them, actually, as a lot of things: as the ex-superintendent of the posh Newton system; as the career educator who took a $27,000 pay cut to come lead their schools; as a white man from the suburbs who beat out a black woman and beloved Cambridge native for the job. The easier glide toward retirement for the 57-year-old Young would likely have been in Newton, where the schools are practically better known than the town itself. Yet Young says he was intrigued by the opportunity to use Cambridge’s vast resources to face down its challenges, which now included skepticism by some that he was the right person for the job. In Newton, a diverse room is one with two types of Jews and a Unitarian. What could Young know about race and class?

“The elephant in the room is diversity,” he said just before the school councils broke off to begin their discussion. “If we end up in a place where the separation is exacerbated, we will have made very poor policy.”

Young’s plan for a new middle school recommends turning some K–8 schools into K–5’s, while another option suggests that a handful of elementary schools may have to close. Some in the minority community fear their schools will be turned into K–5’s or shuttered while the high-performing, largely white K–8’s remain open. In this scenario, the new middle school would turn into a herding ground for black and Latino kids from the projects, further entrenching the segregation. With those fears in mind, Young wanted his audience focused on one question: “What challenges and opportunities exist for educating all of our students? Once again, let me emphasize that word: ‘all.’” To move the school system forward, the race and class division must be faced head-on, he said. “Let’s not pretend it doesn’t exist.”

None of this is what you would expect from the People’s Republic, home to two of the world’s great universities and a city renowned for its progressivism. Maybe that’s because Cambridge is such an easily caricatured place. There’s Brattle Street, Harvard and MIT, all those loony liberals and their Priuses (Obama ’08 stickers still come standard), and even that preppy jerk who, so far as Will Hunting could tell, did not like them apples. Pull away the ivy, though, and complexities abound. While it’s not as if people are walking around with balled fists, there are tensions. The Henry Louis Gates police incident notwithstanding, for years the main source of those tensions has been that Cambridge’s minority kids simply aren’t educated as well as its white ones.

Former Cambridge mayor and current City Councilor Kenneth Reeves, who holds the distinction of being the first black mayor in Massachusetts history, says he often attends each school’s eighth-grade graduation. He recalls watching a morning ceremony at Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., one of the minority schools, and being unimpressed by the students’ canned, unsophisticated speeches. Later that day, he attended a graduation ceremony at the middle-class King Open School, where one student began his speech by saying, “As I ponder the plight of the Palestinians…” Reeves was floored. “You tell me if the eighth grader I saw in the morning is going to be competitive with Mr. Pondering the Palestinian,” he says. In fact, Chris Saheed, the principal of Cambridge Rindge and Latin, the town’s lone public high school, says that his teachers almost immediately can tell which elementary school an incoming ninth grader attended.

It’s not so much that Cambridge’s problems are unique — the achievement gap is a matter of national concern — it’s just that Cambridge, with all its resources and enlightened thought, is itself supposed to be unique. After all, much of its history has been. Independent black communities first settled here during the 18th century, and by the Civil War the city had become an abolitionist stronghold. In 1870, residents even elected a black city councilor. On matters of race and acceptance, Cambridge has almost always led.

The city’s black communities remained in place for decades. Because they were closely tied to specific areas of town, by the 1970s Cambridge found itself with homogenous neighborhood schools. During the riots and rage over busing in Boston, it became clear something had to be done to mix Cambridge’s populations, without prodding from a federal judge. “Boston schools went through a desegregation process that was ugly and terrible,” says Alice Wolf, the state representative from Cambridge, who at the time served on the city’s school committee and chaired its desegregation efforts. Cantabrigians looked across the river and saw sit-ins, marches, and masses of police, and knew they had to desegregate on their own terms, she says. “We went through, essentially, a three-year community process to figure out how to do this.”

She and her colleagues ultimately came up with a “controlled choice” plan, in which parents would list their three most desired elementary schools. Based on the parents’ preference, the city would use a complicated algorithm to sort out which child got sent where, and ensure racial balance.

The plan went into effect in 1981. At first, it was considered a revolutionary success. Far-flung school officials flocked to see Cambridge at work, and cities from the Bay Area to Boston copied the pioneering approach. “Once, when Reagan was president, I went to a meeting where, if you could believe, the Reagan education department people were loving me,” says Wolf, who describes herself as “the most lefty Democrat.”

Early on, though, there were problems. Parents sought to manipulate the system to keep their kids out of certain schools, says Glenn Koocher, who served with Wolf in Cambridge and now is the executive director of the Massachusetts Association of School Committees. Middle-class white parents often recruited students from middle-class minority families so their schools wouldn’t have to dip into the lower socioeconomic realms. “I heard, 25 years ago, every conceivable excuse you could find other than saying, ‘These kids are black’ or ‘These kids are Spanish-speaking,’” Koocher says.

From the start, then, not every school accurately reflected the city’s populace. Since then, as the rules that were supposed to ensure diversity have loosened, the K-8’s have become even less representative. Neighborhood kids started getting preference at nearby schools. Siblings got a leg up, too. Officials became less strict about how closely each school’s racial makeup had to reflect the district’s. In response to a Supreme Court ruling, in 2001 the goal shifted from racial to socioeconomic balance.

Which only made things harder. The state had eliminated rent control seven years earlier, so across Cambridge, old triple-decker apartments were becoming pricey renovated condos, and working-class residents were pushed out. In 1994, the median price of a condominium was $163,770; last year, it was $408,000. Cambridge essentially became a place for only the wealthy and the poor.

Today, roughly 10,000 people, or 10 percent of Cambridge’s population, live in subsidized housing. Without any buffer between those residents and the enlarged wealthy class, discrepancies have become all the more apparent. Steve Swanger, the Cambridge Housing Authority’s director of resident services, says that the last time they counted, two years ago, 38 percent of students in Cambridge schools came from public housing. That’s nearly 40 percent of students coming from just 10 percent of the population.

This stark divide set up the reality Young faces today: a two-tiered system. Wealthy, middle-class parents know how to work it so that their kids get into the higher-performing schools, like Graham & Parks or Baldwin; the less-prosperous parents (who are often single and working multiple jobs) don’t. Parents of lesser means often don’t know to register in time for the process and thus miss out on the good schools, says Michael Alves, who helped implement the choice program in 1981 and still runs Cambridge’s school-selection lottery. And as Haitians, native Africans, Jamaicans, Barbadians, and other immigrants have flooded into town — and mainly into public housing — language and cultural gaps have risen, too. City Councilor Reeves notes that some minority parents, especially in immigrant communities, don’t value academic performance as paramount. They simply prefer a school that is near home, or one where they can feel comfortable with the other parents.

As a result, though a few schools are properly balanced, the Fletcher-Maynard, Martin Luther King, Morse, and Tobin schools are largely minority and at the bottom of the socioeconomic spectrum. The Baldwin, Graham & Parks, and King Open schools are largely white and middle-class. Fletcher-Maynard, for instance, is in the heart of Cambridge’s Area 4, a neighborhood so historically overlooked it’s identified by a number, not a proper name. Two public housing complexes sit across the street, and there are several others nearby. Eighty-five percent of Fletcher-Maynard students are minorities: a mix of African Americans, Haitians, and Latinos, with a few Asian and white kids sprinkled in. Nearly 70 percent of the students qualify for free or reduced lunch under federal programs.

In the most recent round of MCAS testing, no Fletcher-Maynard fifth graders scored as “advanced” in anything, and in English, math, and science, only 26, 21, and 16 percent of students, respectively, scored as “proficient.” Compared with the statewide averages — 63, 54, and 49 percent were either proficient or advanced in those subjects — those numbers are especially troubling. Meanwhile, two miles away at Graham & Parks, where the population is half white and only about 30 percent of students qualify for free or reduced lunch, the fifth graders fared much better: 75, 72, and 71 percent of students were advanced or proficient in English, math, and science.

It’s not a problem of resources. In Cambridge, all the schools have plenty of cash. King, for instance, is one of those schools with poor test scores, but principal Gerald Yung says the first thing he noticed upon arriving nearly a year ago from Worcester was how many more tools he had at his disposal in Cambridge. Sitting in on a recent social studies class, he watched a peppy teacher lead 15 excitable sixth graders. She used a high-tech projector, with a computer standing by. Small classes, resources, engaged teachers — it’s all there. Even in the better-performing schools, free- or reduced-lunch kids test no better than their socioeconomic peers elsewhere in the city. While less-privileged students face many more challenges, some charter schools have still managed to teach them well. Cambridge has not.

That was the reality on everybody’s mind when Young’s predecessor, Thomas Fowler-Finn, retired in 2008 and the school committee went looking for a new superintendent.

Given the history, people quickly noted the distinctions between the two superintendent finalists: Jeff Young, a white man from Newton, and Carolyn Turk, a black lifelong Cantabrigian who had served as interim superintendent. Through March and April 2009, the debate over the two candidates riled the city. Many deeply rooted Cantabrigians — white, black, brown, and otherwise — wondered why a role model like Turk, who had spent more than 30 years in the system and felt like something of an incumbent, was not good enough.

After years of feeling slighted, many minorities identified strongly with her. Turk’s appointment would not only be a huge victory, but she’d also been there and fought the battles — she could be trusted. “I’m sure some people thought you needed somebody who understands exactly who the [students] are in the achievement gap [in order] to best serve their needs,” says Richard Harding, who was elected to the school committee last fall and is its only African-American member.

That sentiment mixed with a potent streak of civic pride. With all the city’s changes, especially in the 16 years since the end of rent control, New Cambridge versus Old Cambridge is the most pronounced friction in town. Newer residents liked that Young came from an aspirational suburb that people move to for the schools but also for the status. Residents with longer family histories, on the other hand, championed Turk as their own. “There’s an element in that community that is very bent on having someone from inside rise to the top,” says the Reverend LeRoy Attles, who spent three decades ministering at the St. Paul African Methodist Episcopal Church near Central Square before retiring last spring. “I guess you have got to live in Cambridge a lifetime to become a Cantabrigian. I was there 30 years and couldn’t qualify.”

The final vote was 5–2. Turk, as she had promised all along, agreed to stay on as Young’s deputy.

“There are people who still won’t talk to me today because of that decision,” says committee member Marc McGovern, who voted for Young. “Some people who I considered to be close friends.”

Before he had so much as signed his contract, Cambridge’s divide became Jeff Young’s problem.

One of Young’s first moves when he took office last summer was to reach out to noted Harvard law professor Charles Ogletree. To the lament of many, Harvard and MIT barely interact with the school district — Harvard actually has a nationally focused program called the Achievement Gap Initiative that, when contacted, seemed only marginally aware that Cambridge has children in it, let alone schools. But Ogletree had sent his kids through the Cambridge system and remains deeply invested in the city. Young joined him, as well as the professor’s daughter and daughter-in-law, both Rindge and Latin grads, for lunch at Changsho, a Chinese restaurant near the law school.

“We had a very candid discussion, and I tried to tell him what I thought would be the steep climb he’d have to make,” says Ogletree, who, in his free time, also dispenses wisdom to his old student Barack Obama. He suggested that Young “reach out to all the parents and children in Cambridge, to let them know his concern about unity. I also told him that he would have to have some difficult conversations with minority parents who often think they’ve been left out of the educational system and their children don’t receive the kind of attention and care and love and respect that is warranted.”

Essentially, Ogletree advised Young to go meet people where they live, and listen to what they had to say before he said too much himself. Meet them at the schools, fine, but also meet them in the churches, parks, and projects. “The most important thing I told him is he has to think differently about Cambridge, about how to establish a relationship with the community.”

Young took Ogletree’s advice. Early in his tenure, he tried to attend at least one faculty, staff, and school council meeting at every school. And at least four nights a week, and sometimes on weekends, he makes it out around town, he says. Per Ogletree’s suggestion, he sought out Attles before the minister stepped down, and then attended his retirement party. When Attles’s successor, Marcellus Norris, invited Young to church to hear the youth choir, he did that, too. Another night, Young went to Ryles Jazz Club in Inman Square to watch school staffers play in a band. High school assistant principal Bobby Tynes, the saxophonist, coaxed Young, who plays guitar, to the stage, where they blasted out “Mustang Sally.” (“I don’t think I humiliated myself,” Young says. “I won’t say I was Eric Clapton.”)

To lead the schools, he says, the first thing he’s got to do is truly understand Cambridge. “It’s an endless parade of events and people, and it’s oddly enough energizing. It’s hard — Friday night I’m ready to crash, but the week goes on. I’m all over the place, and I really enjoy it.”

Harding, the school committee member, for one, has been impressed by Young’s efforts. “I’ve seen Jeff in places that I’ve never seen the previous superintendents. I was at a black church and I saw him there; I see him at basketball games.” Harding also says Young’s frankness distinguishes him from his predecessors.

Indeed, as an outsider free from the baggage of past failures, Young can speak his mind. “As a community we have to look squarely at the gaps in achievement and…say it’s unacceptable, outrageous,” he says. “In some ways it’s even immoral. We just have to do better.”

All of which makes the middle school issue so crucial. For decades, Cambridge has been chewing on whether to move away from the K–8 model, and now, the school committee has mandated Young be the one to finally put the matter to rest.

A new building is hardly an instant remedy for the achievement gap, but there’s been concern about the quality of middle-grades education across the board in Cambridge. In a recent pizza lunch meeting at Rindge and Latin, a group of high schoolers told Young they had barely been challenged until ninth grade. A dedicated middle school, Young and his supporters believe, could provide an opportunity to bulk up the curriculum and fix some of the K–8 shortcomings. There are powerful arguments for making the change. Some elementary schools have just 15 to 30 students in an entire grade, making it hard for them to play sports and join clubs (you try fielding a baseball team with that few kids). Also, teachers are forced to cover a wider range of ages and topics, and, with fewer colleagues teaching the same subjects, say they feel isolated.

Still, support for Young’s plan has been tepid so far. The structure of Cambridge’s schools is a long-standing tradition, and students and parents love how the current system builds community between older and younger kids. And there’s that entrenched concern that a middle school would mostly draw kids from the projects. Young says he’s committed to “social justice,” but Cambridge’s African-American community has heard talk like that before, says Selvin Chambers, who grew up in Area 4’s Washington Elms unit and went on to spend six years as division head for Cambridge Youth Programs and land on the city’s Men of Color Task Force. “When I talk to people, their suspicions are ‘We’ve been down this road before. We’re going to go for the okey-doke,’” he says. “There’s a lot of suspicion and a lot of distrust just about how this all has played out in the past.”

Young has a three-year contract, yet his strategy is to ease Cambridge toward change. Upon taking office, he asked for an extension on the school committee’s timeline for coming up with a middle school plan, and now, at the May 18 committee meeting — originally scheduled as the date for the final vote — he plans to ask for another. In a letter to families, he explained that he wants to tackle the middle school issue along with a reassessment of controlled choice, and that’s why he needs more time.

He’s now tied together two of his biggest challenges. As fraught as the middle school debate has been, the controlled-choice issue promises to be even more so. “Would you send your kid to a school across the street from a housing development? Let’s ask that question,” says Harding. And that could be one of the easier dilemmas.

After all, two of the principles Cantabrigians hold so highly — that parents should be able to choose where their kids go to school and that those schools should be diverse — work most often in opposition. Parents can go on and on about the importance of diversity, but what do they say when it directly affects their child’s education? The answers are neither obvious nor easy. There will be public meetings and debates, and it will be messy. How well Young facilitates discussion will be crucial in determining not just his future, but Cambridge’s as well.

The Thursday night meeting where the superintendent asked the councils from the different schools to move from 12 tables to six may have served as the opening round of that dialogue. They reached no consensus, but consensus “couldn’t happen in two hours with so many people,” Young says. Besides, reaching consensus was never the point. “We heard a lot of very important things from the group,” he says now, “but I think of equal value is that people from different school communities heard from one another.”

Call it a start.