Should You Get the PSA Test?

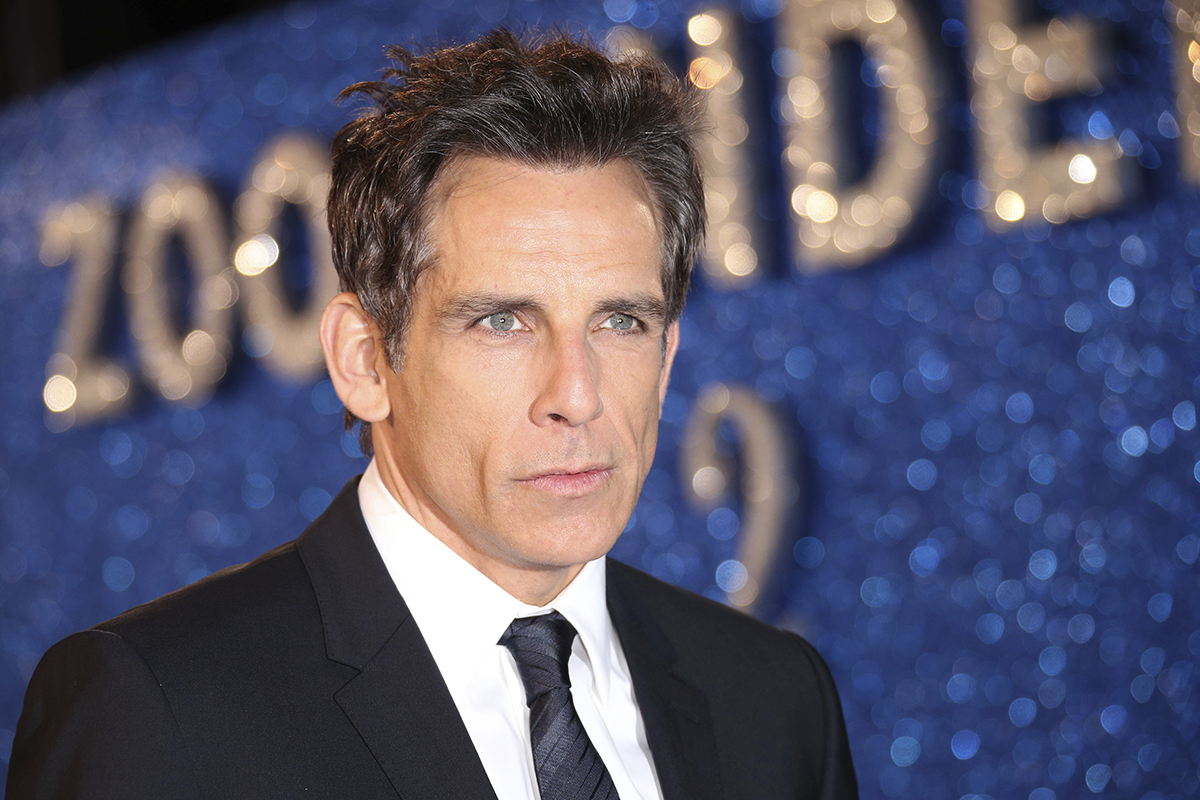

Photo by Joel Ryan/Invision/AP

When Ben Stiller recently announced that he overcame prostate cancer, he wrote in a Medium post that he owes his life to the PSA test, a blood test that measures levels of prostate-specific antigens and can detect prostate cancer. While Stiller praised the procedure, not everyone feels that way.

Currently, the American Cancer Society (ACS) recommends that men who are not at high risk of prostate cancer wait to be screened until age 50, four years after Stiller had his test. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends that men not get the PSA test at all.

Why all the debate?

David Canes, a Lahey Hospital and Medical Center urologist and an assistant professor of urology at Tufts, says uncertainty arises because it’s hard to tell when PSA levels are problematic. A benign growth can still raise PSA levels; even a malignant growth can be so slow-growing that detection of the cancer leads to unneeded stress and biopsies. Those biopsies can sometimes be more harmful than the tumor itself—while a slow-growing cancer doesn’t pose an immediate threat, biopsies can cause bleeding or even bloodstream infections that require a hospital stay.

Still, Canes says there’s a place for the PSA test, though he specifies that men between the ages of 55 and 69 are its key demographic. “We don’t want to throw out PSA screening for all men and risk not being able to identify those men who really need our help,” Canes says.

That said, Canes notes that “no decision should ever be made based on a single blood test.” Often, a second PSA test will show lower levels than the first. Even if results stay the same, other tests, such as MRIs, can be used to confirm a diagnosis.

Canes also believes in active surveillance: only treating aggressive prostate cancer and simply monitoring benign and slower-growing tumors. A September study supports the notion of active surveillance, finding that men who carefully tracked their cancers lived just as long as those who immediately underwent surgery or radiation.

“If doctors can demonstrate they can be trusted to do the right thing on behalf of their patients and only selectively treat those prostate cancers that seem like they’re going to be potentially deadly, and only do active surveillance for the rest, men’s lives will be saved who need saving and people won’t be treated unnecessarily,” Canes says.

Canes also says the USPSTF’s suggestion—that no one undergo PSA screening—could have repercussions. Projections show, he says, that without PSA screenings, rates of metastatic prostate cancer could rise to levels seen before the PSA test was developed.

“When you make a decision about how you’re going to screen, you don’t see results for 10 to 20 years because it’s a slow-growing cancer,” Canes says. “Policy implications from today will take a while to have an impact.”