Throwback Thursday: The Caning of Charles Sumner

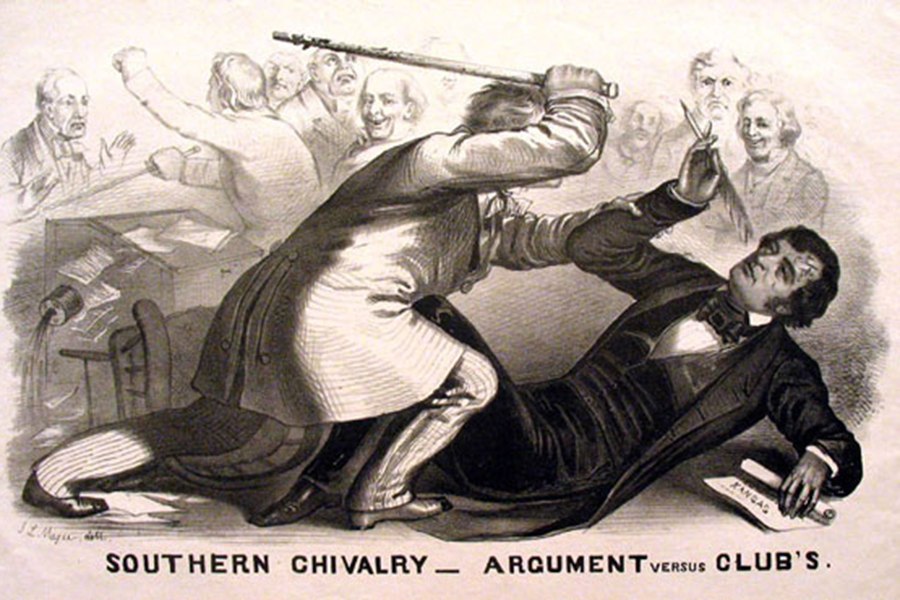

After delivering a fiery anti-slavery speech on the Senate floor, the Massachusetts official was beaten by Rep. Preston Brooks of South Carolina.

Photo via Wikimedia Commons

If Congress today seems rife with friction, factions, fire, and fury, it’s nothing compared to the chambers’ disposition leading up to the Civil War.

Abolitionist Republicans and pro-slavery Democrats initially opted for rhetorical battles to try to remedy the ideological chasm between the two parties in the mid-19th century. But on May 22, 1856, the ire directed across the aisle erupted into physical violence when Rep. Preston Brooks of South Carolina beat Massachusetts Sen. Charles Sumner unconscious with a cane.

A few days before the attack, Sumner delivered a passionate speech denouncing the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which effectively repealed the Missouri Compromise and allowed people in the new territories to decide whether they would allow slavery. He called out two Democratic senators in particular, Stephen Douglas of Illinois and Andrew Butler of South Carolina, for their roles in crafting the legislation. He referred to Butler, who was not in the chamber at the time of the speech, as taking “a mistress … who, though ugly to others, is always lovely to him; though polluted in the sight of the world, is chaste in his sight—I mean the harlot, Slavery,” according to Senate records.

Butler’s family was none too pleased with the characterization, and the senator’s cousin, Rep. Brooks, took matters into his own hands.

On that fateful May afternoon, Brooks entered the Senate chamber and repeatedly bludgeoned Sumner with his gold-topped cane. The head trauma stunned Sumner, and he struggled to defend himself against the attack. Brooks levied the blows with such force that his cane eventually snapped, and while some congressmen attempted to break up the melee, others encouraged Brooks’ violence. After the South Carolinian was finally restrained, Sumner regained consciousness and received necessary medical attention. The brutal, bloody affair is a stain on Congressional history and foreshadowed the brutality of the Civil War.

Though Brooks received plaudits for the assault in the South, he resigned from Congress in July 1856, and died in January 1857. Sumner, meanwhile, experienced lingering head pain and would not return to his perch in the Senate until 1859.

Several sites around Boston honor Sumner, including a plaque in Beacon Hill denoting his birthplace. The senator’s home at 20 Hancock St., which is a few blocks from the spot where he was born, was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1973. And two statues of the anti-slavery advocate also dot the Hub, one in the Public Garden and one in Harvard Square.