He Died Guarding a Captured Slave in Boston. Does He Really Deserve a Memorial?

The U.S. Marshals Service honors the memory of a man who died on the job for a shameful cause.

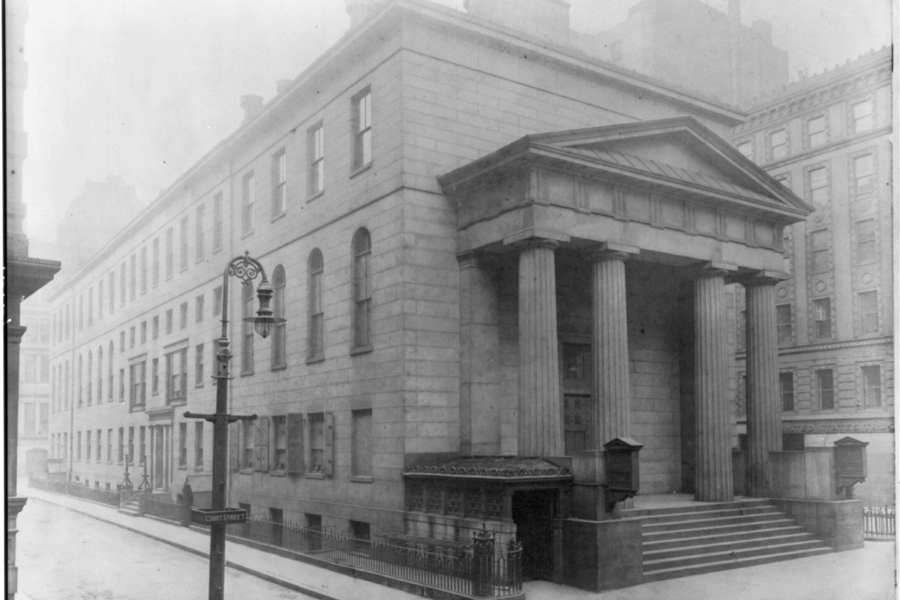

Boston courthouse c1909 photo via Library of Congress

James Batchelder, historians say, never asked for any of this. But nevertheless, one night in 1854, the 24-year-old Irish immigrant found himself at the door to Boston’s courthouse, guarding a captured slave from a mob intent on freeing him.

The controversial federal Fugitive Slave Act was at that point in full force, requiring that runaway slaves caught even in abolitionist states like Massachusetts be detained and returned to the slave-holding south. An escaped slave named Anthony Burns had been captured in Boston and ordered held in the city’s federal courthouse, and Batchelder had been called into service as a marshals guard. His job was to keep at bay anyone who might try to set Burns free, so as a crowd of hundreds tried to force its way into the courthouse to free Burns, they found Batchelder standing in their way. In the scuffle that followed, he was shot, and soon he was dead. It was a shameful assignment, the kind that put him firmly on the wrong side of history, and it was the last thing he would ever do.

Batchelder’s name lives on in history books, and it belongs there. His death is considered to be among the events surrounding the Anthony Burns case that energized the slavery debate—creating so much buzz that a reported 50,000 Bostonians later lined the street as Burns was ultimately led in chains to a ship headed for Virginia—and set the nation on a path to the Civil War.

But you can also find it somewhere else: On the U.S. Marshals Service’s online memorial, a so-called Roll Call of Honor for more than 200 marshals who “have given their lives in service to their nation” dating back to 1794. “We honor their memory and their sacrifice,” reads a post on the site, which is run by the Justice Department. Batchelder is also listed on a “Wall of Honor” at the Marshals headquarters, and he’ll be represented in the privately run U.S. Marshals Museum in Arkansas, which is under construction and set to open in 2020.

Does it belong there? That’s the question I received in the mail recently from a tipster who has asked to remain anonymous, for reasons unspecified, but believes it’s time to take Batchelder’s name off such pedestals. As far as I can tell, the little-known web page hasn’t been discussed much in Boston. (It did receive some attention in 2013 on the website for Reason, the libertarian magazine, but basically nowhere else). But the city and state right now are at pains to confront ties to racism and slavery that are hidden in plain sight—we changed the name of Yawkey Way last year, ripped a Confederate monument off its perch on a harbor island in 2017, worked to change Dudley Square’s name to Nubian Square, and may soon eradicate the state flag. So it’s important to take a close look at what exactly is being celebrated here, and what message we’re sending police—or, say, ICE or Border Patrol agents—about whether history will hold them accountable for their actions or uncritically honor them for their service.

First, some context: Historians say Batchelder was a poor, likely illiterate laborer from Ireland who may have been forced into the job against his will. The Marshals likely ordered him to take the job, and Batchelder would have faced steep fines under the Fugitive Slave Act for refusing. If he’d had any strong feelings about slavery one way or another, there’s no record of it. For that reason, according to historian Albert Von Frank, Batchelder’s story is best understood as a tragic one.

“To be clear, he was spotted on the street in the course of his normal work and his services were commandeered by [U.S. Marshal Watson Freeman] in impromptu fashion. The marshal had a legal right to do that,” Frank, who wrote a book about Burns, tells me in an email. “The problem, in other words, was with the Fugitive Slave Law, not with Batchelder himself.”

Batchelder is not alone among honorees with a disturbing backstory. In 1851, Maryland’s Edward Gorsuch died hunting for his escaped slaves in Pennsylvania, also under the authority of the Fugitive Slave Act. He’s immortalized as the third entry on the U.S. Marshals’ list.

The Marshals Service itself is aware of this complicated history, and to its credit, does not ignore it. There’s even a page on its website dedicated to addressing the work marshals did to keep the slavery machine rolling. But the Marshals also stress that its officers were later on the right side of history, protecting black children on their way to newly desegregated schools, and facing down a segregationist mob at the Ole Miss Riot of 1962. “The agency’s storied past included a few duties that would be considered morally unthinkable in America today, but [marshals] also had a hand in correcting these same injustices,” David S. Turk, the Marshals’ official historian, tells me in an email. He says that despite the adulatory tone of the Roll Call of Honor, it “does not differentiate by any other standard than duty at the time of death.” So, he argues, “to not include James Batchelder due to moral judgment would nullify historical accuracy and transparency.”

Batchelder’s defenders at the time saw him at worst as a man who just happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time, and labeled the mob and the activists who incited it “murderers,” as the Rochester Daily American put it. “What had Batchelder done,” the paper asked after his death, that would lead the crowd of abolitionists to “steep their souls in his blood?”

Frederick Douglass, meanwhile, had zero sympathy for Batchelder. In a fiery essay published just a week after the Bostonian’s death, Douglass wrote that by taking the job and playing a role, however small, in the institution of slavery, Batchelder “labelled himself the common enemy of mankind” and therefore had it coming:

[W]hen James Batchelder, the truckman of Boston, abandoned his useful employment, as a common laborer, and took upon himself the revolting business of a kidnapper, and undertook to play the bloodhound on the track of his crimeless brother Burns, he labelled himself the common enemy of mankind and his slaughter was as innocent, in the sight of God, as would be the slaughter of a ravenous wolf in the act of throttling an infant. We hold that he had forfeited his right to live, and that his death was necessary, as a warning to others liable to pursue a like course.

Here in the future, we don’t have to decide whether he should have lived or died, but we do have a choice in whether to honor him for his service, and some contemporary thinkers refuse to let him off the hook. “I don’t buy” the argument that he was just following orders, says Clennon King, the Boston filmmaker who this year successfully pushed the Martha’s Vineyard community Oak Bluffs to remove a plaque honoring Confederate veterans, “any more than Jews would tolerate the argument that Nazi soldiers who fled to South America after WWII were just doing their job, and shouldn’t be held accountable.”

But the Marshals aren’t the only group who’ve seen fit to sing Batchelder’s praises. He’s also honored on something called the Officer Down Memorial Page, a website that is apparently dedicated to the memory of every dead law enforcement officer in America. The page’s listing for Batchelder notes that he died “attempting to keep a mob of citizens from taking a prisoner at the courthouse,” while also acknowledging that the prisoner in this particular scenario was, you know, a fugitive slave. Five people, each of them self-identifying as cops, have left tributes to the fallen marshal in the website’s comments section. “To have faced a mob as a law officer, especially in the days of only the gun and the badge—and little else, is the very core of bravery no matter the circumstances,” reads one of them, apparently from a retired Pennsylvania State Police corporal. “To have taken a bullet in the name of the law deems one a hero among heros [sic]. Long live such bravery and honor.”

So it’s true that these permanent memorials matter a whole lot to some people, even if they aren’t as tangible and prominent as, say, a statue of Robert E. Lee. The fact remains that somewhere, in some way, the feds and a loose collection of fanboys are celebrating a man whose last act was preventing the rescue of a slave. Whether you’re OK with that is your call, but you can’t ignore that it’s happening.

Was Batchelder a casualty of history? Maybe. Was he a hero? I don’t think so. So what do we do now?

Anthony Burns image via Library of Congress