City of Spies

As the FBI continues hauling university scholars and researchers off in handcuffs for their work with the Chinese, academics all over Boston are asking: Am I next?

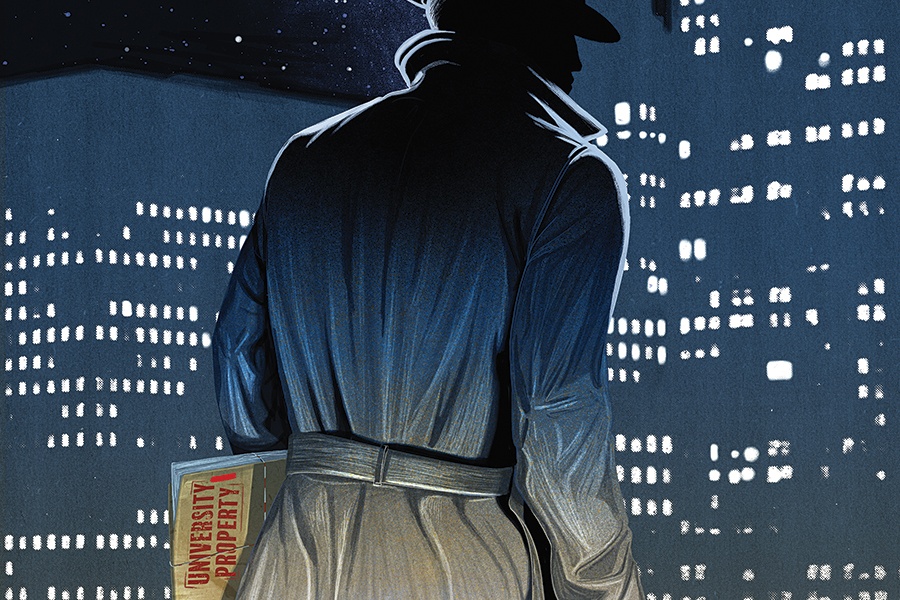

Illustration by Jonathan Bartlett

Charles Lieber had a brilliant mind. So it was widely assumed, at least among the rarified upper echelons of the scientific community, that there would come a day when the esteemed Harvard nanoscientist would receive an early-morning surprise from an unexpected caller—someone with a Norwegian accent telling him he had won a Nobel Prize. No one, though, could have imagined the jolt he received on campus one cold January morning this year, just the second day of the spring semester, when FBI agents stormed the brick building that houses the Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology clutching an arrest warrant with his name printed on it.

Surrounded by men with guns and badges, Lieber found himself listening to the unmistakable clink of handcuffs locking around his wrists. As seven black vehicles simultaneously barreled down a winding road toward the professor’s modest Lexington home to search it, agents in Cambridge loaded Lieber into a car and whisked him across the Charles to the Moakley Courthouse on the Boston waterfront, where federal prosecutors were waiting. His alleged crime? Failing to report—and later denying to government officials—that he was receiving research funding directly from a Chinese university.

Lieber had long been involved in a lucrative and secret deal, according to the charging documents, which alleged that the head of Harvard’s chemistry department was also a member of the Thousand Talents Plan, a Chinese-government-sponsored recruitment initiative designed to reverse the country’s decades-long brain drain. As part of the agreement, Lieber was eligible to receive a salary of up to $50,000 a month, $158,000 for personal expenses, and the sum of $1.74 million in exchange for building a joint lab between Harvard and the Wuhan University of Technology (WUT) in China. The goal, according to intercepted emails between Lieber and a contact at the Chinese university, was to cultivate young Ph.D. students, set up international conferences, and apply for patents and publish papers in WUT’s name. While it’s certainly not illegal to take money from a foreign university, it is a federal crime to lie about it to U.S. government agencies that are also providing you funding, as the FBI alleges Lieber did. Two days after his arrest, Lieber, who is facing up to five years in prison, posted a million-dollar cash bond and surrendered his passport to the court.

Lieber is hardly the only academic who’s awoken over the past few months to find themself staring down the barrel of a major federal effort targeting Chinese espionage. Several weeks before Lieber’s arrest, Zaosong Zheng, a 29-year-old Chinese cancer researcher who was working at Beth Israel Deaconess, was making his way to his gate at Logan for a Beijing-bound flight when customs agents pulled his checked baggage aside for inspection. His nationality, destination, and place of work—as listed on his visa—set off alarm bells for an agency constantly on the lookout for Chinese theft and spying. Their hunch was confirmed the moment agents looked inside one of Zheng’s bags and found 21 small vials containing DNA samples stuffed into a sock. In a scene ripped straight from the pages of a spy thriller, officers raced to Zheng’s gate and intercepted him on the jetway just as he was about to flee the country with his secret cargo. According to an FBI agent’s affidavit, Zheng allegedly admitted later that he stole some of the vials and surreptitiously replicated others from someone else’s research at the lab, all with the goal of continuing his research and publishing the findings under his name in China.

The day Lieber was arrested, authorities also released an international arrest warrant for Yanqing Ye, a former Boston University graduate researcher who allegedly hid the fact that she was a member of the Chinese military when she applied for a U.S. student visa, claiming she’d been collecting information for her superiors back in China.

These were the first three cases in Massachusetts to emerge since the Department of Justice launched its China Initiative in late 2018. Its mission? To counter the widespread theft of technologies and intellectual property that the government believes is powering China’s quest to surpass the United States as the world’s leader in science and technology. In fact, if you ask Massachusetts U.S. Attorney Andrew Lelling, he’ll tell you that Chinese espionage is “the most serious national security issue that no one talks about.”

Here in Boston, we are fast becoming ground zero for that threat. Experts say the city’s countless universities, hospitals, biotech startups, and defense contractors have given us the dubious distinction of being one of the nation’s prime targets for economic and military espionage. As a result, Lelling—along with four other U.S. attorneys in districts that, like Boston, are potential hotbeds of Chinese espionage—was chosen to lead the charge.

Perhaps fitting given Boston’s demographics, this trio of recent cases all involved academics. But it’s not just here that university campuses are emerging as the government’s latest and most controversial frontier for rooting out Chinese espionage. From West Virginia to Kansas to Tennessee, scholars and researchers have been investigated, surveilled, and arrested.

Frustrated by what they perceived to be a lax response to this threat in the past, many China experts have applauded Lelling’s latest crackdown; after all, protecting the knowledge generated in academia is essential to securing our place at the top of the innovation food chain, not to mention as an economic juggernaut. Some, however, say the recent uptick in federal prosecutions unfairly targets the large population of Chinese and Chinese-American scholars working in U.S. academic labs as well as those, like Lieber, who work closely with scientists from China. They worry that law enforcement’s newfound zeal could create a bigger problem than the one it seeks to solve. After all, limiting international collaborations with China, starving universities of Chinese funding, and scaring away Chinese scientists who have long been the greatest pool of talent for our university labs will only benefit China by handicapping our scientific efforts.

What everyone can agree on, though, is that the arrests of Lieber and two other local academics signaled a clear escalation in the U.S. trade war with China—one trained right on Boston’s ivy-draped college campuses. Lelling has demonstrated that he is unafraid of pursuing the theft of intellectual property, much of which is produced thanks to taxpayer-funded government grants. Whether it ultimately protects Boston’s IP or topples us from our place as a global leader in science, the offensive has the potential to upend how research is done on Boston’s campuses—and in the process fundamentally change one of the most innovative academic communities in the world.

Harvard nanoscientist Charles Lieber is thus far the most high-profile academic under investigation by the U.S. Department of Justice as part of its new China Initiative. Lieber is accused of lying to federal authorities about money he was allegedly receiving from a Chinese university. / Photo by Jonathan Wiggs/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

There are spies among us—that much we know. They are living unnoticed in tony suburban towns outside of Boston, working inside some of our cutting-edge industries, and teaching at our world-class universities. In 2011, for instance, a Devens-based energy technology company named American Superconductor Corporation lost a billion dollars in shareholder equity and was forced to cut 700 jobs. Why? Because Sinovel, a Chinese wind-turbine-manufacturing company that was one of American Superconductor’s high-dollar clients, offered one of the company’s engineers $1.7 million, an apartment in Beijing, and entrée to women in exchange for giving them access to the U.S. company’s proprietary technology. Once Sinovel had the technology, it canceled all of its orders, which it no longer had any use for. In 2018, meanwhile, the U.S. government charged a Chinese national living in Wellesley with falsifying documents to send sonar systems and hydrophones—which have export restrictions on them because they can be used in anti-submarine warfare—to a military university in China. Both of these incidents are clear local examples of how Chinese spies came to town and threatened U.S. economic and military supremacy.

The cases against Lieber, Zheng, and Ye fit into a slightly different fedora and trench coat, but, if you believe the FBI, they’re just as insidious. On the day of Lieber’s arrest, Joseph Bonavolonta, the FBI special agent in charge of the Boston field office, took to the podium at the front of a low-ceilinged room in the federal courthouse in the Seaport. While news cameras flashed, he told reporters that all three defendants were “manifestations of the China threat” posed by so-called nontraditional collectors: individuals who are not spies but professors, students, and other local residents used to gather valuable information. “All of the individuals charged today,” he said, “were either directly or indirectly working for the Chinese government, at our country’s expense.”

Boston’s professors and researchers, China experts say, are a key component of China’s strategic plan to turn itself into a country that doesn’t simply manufacture other nations’ innovations, but one that develops the innovations and produces them itself. For many years, China has employed illegal means of working toward this goal, including stealing IP and reverse-engineering products. That approach has its limits, though, says James Mulvenon, a Chinese linguist who works closely with U.S. government agencies. Chinese engineers have proven adept at reverse-engineering, he says, but they haven’t appeared to “fully understand the organic sort of innovation that was at the heart of the product.” That’s why, he says, China has begun investing in hundreds of recruitment initiatives, including the Thousand Talents Plan that Lieber was allegedly a part of. The goal of that program, he says, is to bring people to China and mine them for the intangible information they possess about particular technologies. “Professor Lieber is a good example,” he says, “because it’s one thing to steal the plans or the schematics of how to do really high-end material science, but it’s even better if somebody explains it to you.”

On the face of it, a talent-recruitment program doesn’t sound nefarious, but experts say they’re often hooks that allow the Chinese government to reel people in and squeeze them for sensitive or proprietary information. Roy Kamphausen, a former Department of Defense official who is now president of the nonpartisan, nonprofit National Bureau of Asian Research, says that programs like these, and the generous support they offer, are used to create relationships with Chinese scholars—and non-Chinese scholars such as Lieber—that the Chinese can later leverage to convince participants to provide access to specific IP. He says that there is a perception, real or not, among Chinese-Americans that there are limits to their professional advancement in the U.S. because of racial biases. The Chinese government, he says, manipulates these resentments and plays the “nationalist card” to entice them to go to China and bring IP with them.

Other times, the Chinese government will resort to even more pernicious means. State officials, Kamphausen says, take advantage of the fact that so many Chinese and Chinese-Americans working in the United States in strategic industries and fields have family in China. “The Chinese system can be brutal in the way it can pressure families,” he says. “They’ll say, ‘Listen, your uncle, your nephew, your niece—whatever the case may be—needs to help us, or your life will be more difficult.’”

Meanwhile, Mulvenon and others have spent the better part of the past decade trying to make U.S. government officials aware of the dangers posed by talent-recruitment programs. It wasn’t until 2019, however, that people finally started paying attention. That year, a Senate committee investigation found disturbing cases of those in talent-recruitment programs acting suspiciously: setting up shadow labs in China that mimic the government-funded research they are pursuing in the United States, removing tens of thousands of electronic files before leaving for China, and filing patents based on research funded by the U.S. government, among other problematic behaviors.

That same year, the National Institutes of Health announced it was investigating 180 scientists because of undisclosed relationships with Chinese universities. The National Science Foundation, the Department of Energy, and other U.S. government grant makers did the same. Then the FBI admitted it had been asleep at the wheel and began focusing on universities, investigating and arresting academics for failing to disclose their participation in the Thousand Talents Plan. None of them, however, were as prominent or well known as Harvard’s Lieber.

Back in April 2018, several Department of Defense G-men knocked on Lieber’s door at Harvard. Over the years, the U.S. government had given Lieber $8 million to fund research at his university lab—an interconnected network of offices; so-called wet labs, where experiments are undertaken; and dry labs, where computational work is done—that spans two floors and two buildings within the chemistry department complex. During the visit, the Thousand Talents Plan came up in conversation. Lieber told the government officials that he had been to China and was familiar with the Chinese program, but was not a participant.

After his guests left, Lieber felt rattled. That night, he tossed and turned, unable to sleep, worrying about the encounter while questions swirled through his mind. Months went by and nothing came of it. But the DOD investigators weren’t the only ones poking around Lieber. In November of that year, officials from the NIH, which had also funded Lieber to the tune of some $10 million, reached out to Harvard with similar questions. When Harvard called Lieber to clear things up, he again denied his participation in the Thousand Talents Plan and said he hadn’t had a formal relationship with WUT since 2012. The Chinese university, he told them, was falsely exaggerating their relationship. Surveillance of his email, though, indicated otherwise and formed the basis for his arrest more than a year later.

Lost in the hoopla surrounding his dramatic fall was the fact that Lieber has not been accused of espionage, nor was there any evidence that he transferred sensitive information to China. Even Lelling said he doesn’t think Lieber is a spy. And by the way, there is no evidence behind an Internet conspiracy theory that Lieber invented the novel coronavirus and sold it to the Chinese. Nonetheless, making false statements to federal officials is a crime—even if the action the person lied about doesn’t turn out to be unlawful. (Neither Lieber nor his attorney responded to numerous interview requests.)

Not everyone is convinced that hauling academics like Lieber off in handcuffs is a good idea. Critics of recent cases such as Lieber’s accuse the government of—quite literally—making a federal case out of what in many instances is merely a professor’s failure to diligently fill out paperwork or a desire to hide moonlighting from an employer. These infractions might ordinarily get academics reprimanded by their superiors, fired, or banned from receiving federal grants—not, critics stress, arrested and thrown in jail. “Treating these university professors like felons is a terrible injustice,” states Peter Zeidenberg, a Washington, DC-based attorney with Arent Fox and former Middlesex County prosecutor who says he is currently representing “dozens” of Chinese scientists facing these kinds of investigations and charges. Like with Lieber, he says, none of these recent cases involves accusations of passing sensitive information to the Chinese.

What’s more, the rules surrounding academic partnerships haven’t always been clear, Zeidenberg says. For years, while universities encouraged professors to pursue international collaborations, they did little to emphasize the importance of funding disclosures. Suddenly, Zeidenberg says, making these disclosures—even about relationships formed years ago—is paramount. “They’ve changed the paradigm midstream, and they go back and say, ‘Well, let’s see what you reported in 2016 or 2008.’ At that time, this wasn’t on anybody’s radar,” Zeidenberg explains. “And now they’re saying that that failure [to report] is critical and it’s not just, ‘Hey, you’re doing it wrong and if you do it wrong again you could lose your job.’ They’re saying you could go to prison for it.”

Perhaps the gravest concern among critics is the way this paradigm shift has almost exclusively affected Chinese and Chinese-American researchers. When encouraged by their employers to set up international collaborations, these academics unsurprisingly looked to China, given their language skills and connections. Now, however, they are paying the price for it. “Since China is the new strategic competitor,” says Aryani Ong, a former civil rights attorney and a Washington, DC, activist on this issue, “all interactions with Chinese foreign nationals elevate these violations onto a different plane.” In other words, says Andrew Kim, an attorney and law professor currently at South Texas College of Law Houston, Chinese scientists are now facing scrutiny for the new crime of “researching while Asian.” It is the latest incarnation of what he believes is the U.S. government’s biased targeting of Chinese people in the name of battling economic espionage. As proof, he points to a study he published last year in the Cardozo Law Review based on a sample of 187 individuals charged under the Economic Espionage Act. From 1997 to 2009, 17 percent of defendants were of Chinese descent; after 2009, the rate tripled to 52 percent.

History has shown that many of the cases brought by the U.S. government are weak—especially, it turns out, when the defendant is Chinese. Kim’s study found that one out of five Chinese defendants were acquitted, had their charges dropped, or were pushed to take a plea of a lesser charge, such as making a false statement. That happened nearly twice as often as it did for non-Asian defendants, 11 percent of whom were acquitted—meaning, Kim says, that authorities were more often bringing weak cases against Chinese defendants. Since the study’s completion, some high-profile cases against scientists have also fallen apart, to the embarrassment of the government. Zeidenberg, who is also a former U.S. attorney, is not surprised. “This is what happens in law enforcement in general when you incentivize agents and prosecutors to bring certain kinds of cases. You end up bringing junk cases.” Lelling defends the government, saying that in any new crime-fighting endeavor there is a learning curve for building cases.

Meanwhile, in the university world, Chinese and non-Chinese professors alike are increasingly confounded by the whole concept of academic spying. After all, while some universities have labs working on highly classified research, such as MIT’s Lincoln Laboratory, the vast majority of university research, including Lieber’s, is basic research, which means it doesn’t yet have commercial applications. What’s more, scientists point out, the whole purpose of academic research is to publish their findings. In fact, their jobs depend on it. No one needs to spy on them, they say: All of their findings appear in academic journals for everyone to read—even people in China.

From left, the FBI’s Joseph Bonavolonta, Michael Denning, director of field operations for the Boston office of U.S. Customs and Border Protection, and U.S. Attorney Andrew Lelling announce the first three cases to emerge in Boston as a result of law enforcement’s China Initiative. / Photo by Katherine Taylor/Reuters

While reporting this story, I set out to ask Chinese scholars and researchers working in Boston what effect, if any, the FBI’s recent focus on academia was having on campus and on them. The conversations I didn’t have told me just about as much as the ones I did.

I emailed and called academics relentlessly, and even spokespeople for local associations of Chinese scientists, only to get radio silence. I lurked on campuses for hours, only to have doors shut in my face and people scurry away when I introduced myself. When I asked a researcher to find out if the Chinese postdocs in his lab would be willing to speak with me, they all told him no. Someone I know at Harvard agreed to ask a colleague who works on China issues if he would approach some Chinese scholars on my behalf, but only at an upcoming conference where he could do it in person because, given the sensitivity of the issue, he didn’t feel comfortable putting anything in writing.

After several weeks of hunting, I finally found professor Shuguang Zhang, a molecular biologist who researches how peptides in the body facilitate drug delivery at the MIT Media Lab. As I sat down with him in his small book-cluttered office, he gave a name to the reactions I was getting: fear. People are flat-out scared, he told me. When I asked him if he had been approached by FBI investigators, he said, “Not yet.”

Months before the spread of the coronavirus would lead to targeted acts of harassment and aggression against rank-and-file Chinese-Americans, academics were already feeling they were the victims of racial profiling by the government’s China Initiative. For his part, Lelling insists that the Department of Justice is not engaging in racial profiling. “The government isn’t surveilling thousands of Chinese students. We aren’t targeting the Chinese because they are Chinese. We follow the behavior, not the individual,” he says, adding that logically a lot of the targets will be Chinese because “China is in the midst of a concerted effort to steal U.S. technology.” The FBI’s Bonavolonta echoed Lelling’s sentiments and emphasized the enormous outreach efforts the bureau is undertaking to brief local universities on real, documented cases of academic espionage and to get them thinking about “what their crown jewels might be”—i.e., what the Chinese government might be after on their campuses, and how to protect it. In other words, the FBI says the initiative isn’t just about rounding people up and arresting them; it’s about educating people about a threat that is so long-term that it’s difficult to even perceive.

Despite the critiques, Lelling and Bonavolonta have a bevy of strong supporters. Furthermore, Yasheng Huang, a Chinese professor at MIT’s Sloan School of Management who studies entrepreneurship and U.S.-China relations, says the situation is more complicated—that if anything, the government is practicing political, not racial, profiling. At the same time, though, he says that the fear among Chinese scholars is understandable considering the history of failed federal cases and the current administration under which this initiative is being carried out. President Donald Trump, after all, has said he thinks nearly all Chinese students are spies.

That fear will likely grow as the DOJ initiative gets an injection of spy craft. Bonavolonta says that in September, the FBI launched its counterintelligence taskforce for Chinese espionage. Modeled on the counterterrorism task force launched after 9/11, intelligence agencies from the Department of Defense are now embedded with the FBI to pursue these cases.

There’s also the potential for the initiative to become far more sweeping. Mulvenon, one of the China experts who originally sounded the alarm on the Thousand Talents Plan and who works closely with law enforcement, is now training his sights on other educational and professional organizations, contests, and nonprofits that he says he’s found are engaging in the transfer of information to China. His list of Boston organizations is 110 entries long and includes some fairly unthreatening-sounding groups, including the Cambridge Center for Chinese Culture, Chinese student associations on college campuses, and the Chinese Actuarial Club.

Even in its early stages, the crackdown already seems to be taking a toll on innovation in Boston and beyond. China has long been the biggest talent pool for recruiting people to do the time-consuming and labor-intensive experiments that produce our scientific breakthroughs, Huang says. The Media Lab’s Zhang says virtually all of the top labs at MIT have postdocs from Chinese universities, including his own. At least it did—recently he has not been able to find any Chinese researchers who want to work in his lab. Many are going to Europe instead, something he attributes to the anti-Chinese sentiment coming from the Trump administration. It’s a strategy we pursue at our own peril: Without Chinese researchers, he fears, scientific progress in the United States will grind to a halt.

Meanwhile, some critics of the government contend that law enforcement’s recent vigor actually encourages brain drain from the United States to China, something that will only make us less competitive. Chinese American scientists who have spent “decades in the U.S. making valuable contributions are reportedly leaving because they feel that the badges of their ethnic background bring them suspicion,” says the activist Ong, who adds that “Chinese American parents in the U.S. are reportedly advising their children not to get into science, or work for the federal government, particularly if it requires security clearances.”

A top cancer researcher from the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston who came under scrutiny for her ties to Chinese universities, for example, has since moved to a college in China. Weihong Tan, a University of Florida scientist who left the country because of investigations into his participation in the Thousand Talents Plan, recently developed a successful test for COVID-19—for the Chinese university where he now works. And at MIT, a postdoctoral researcher questioned by the FBI about his participation in the Thousand Talents Plan last year has since returned to China.

It isn’t just a loss of people, of course: With universities putting more restrictions on Chinese funding and some researchers even refraining from pursuing such money, there are fewer resources to do the most innovative work on our campuses. A scientist at MIT, who asked me not to use his name for fear he would be targeted, said there are now long delays at the school for approving research funding from Chinese companies. He fears they ultimately will be denied, something that would force him to cut jobs at his lab.

Zhang, for his part, says he won’t seek any collaborations with Chinese universities—in fact, he recently turned one down. When I asked why, he answered me with two words: Charles Lieber.