The Designer of the Hancock Tower Is About to Change Boston’s Skyline Again

The Four Seasons Hotel & Private Residences at One Dalton is nearing completion.

Image courtesy of Pei Cobb Freed & Partners

Few people in this world can say they’ve affected the skyline of their home city, but 91-year-old architect Henry Cobb is about to have two iconic buildings to his name. In 1976, he designed the Hancock Tower, still the tallest building in the city, and at the time, one of the only skyscrapers in Boston. Building began in 1968, and by the time it was completed, it soared more than 40 feet above its nearest neighbors.

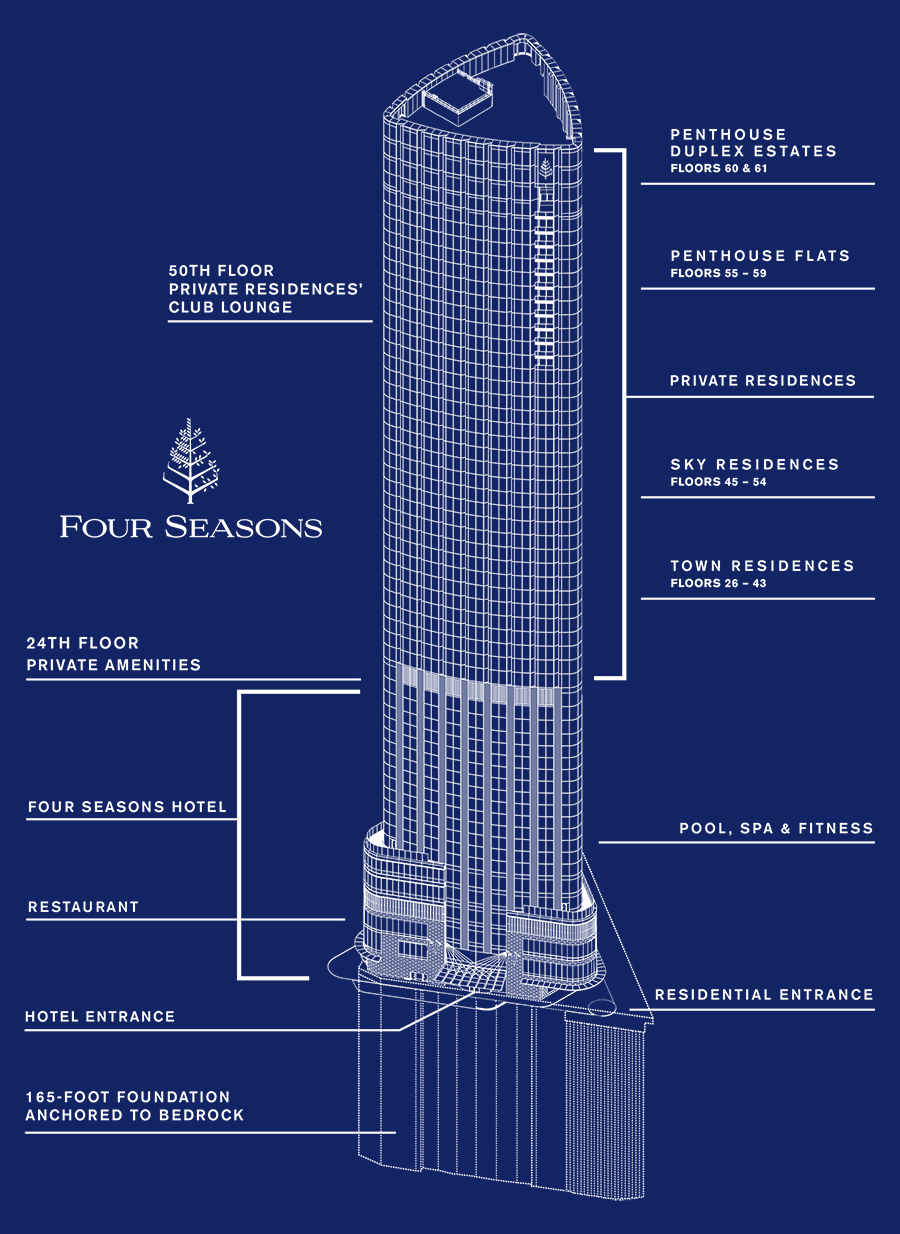

But Cobb’s latest building will soon rival it. One Dalton, set to open as the Four Seasons Hotel & Private Residences later this year, will rise 61 stories in Back Bay. One Dalton won’t reach quite the heights of Cobb’s earlier effort, but it will be the tallest residential building in New England at 740 feet high.

Like the Hancock, it too will sparkle and shine on the skyline, thanks in part to Cobb’s decision to dress the facade entirely in glass. When it’s completed, residents will have an unparalleled view of the city from the tower’s floor-to-ceiling glass walls, with a panorama spanning from Boston Harbor to the Cape in certain units.

“I don’t believe that anything approaching this combination of material and technical detail has been done up to now,” explains Cobb, who has designed dozens of buildings around the world, including Boston’s Harbor Towers and Moakley Courthouse. But building with glass, says Cobb, is no simple matter.

“This is not just kind of offhand, ‘Yeah, let’s do an all glass building,’ and now it’s done,” says Cobb. “It’s very, very precisely calibrated.”

While designing the John Hancock Building, now known as 200 Clarendon, Cobb sought to build it with the largest glass panels possible. Though there were challenges with the glass in the building’s early stages—during construction, windows broke and crashed to the street on windy days—Cobb is game to try it again with the help of improvements in glass technology.

One Dalton will be clad in huge 12-foot glass panels, each of which are composed of three layers. The first, or outermost sheets, are tinted grey to provide the residences with naturally colored daylight and reduce glare from the sun. Plus, from the outside, the building won’t appear overly transparent, preserving privacy and maintaining the uniform character of the facade.

This grey glass, which is only produced in California, has to be shipped to Europe and combined with clear glass layers from Spain and Hungary before being shipped again to Toronto, Canada. There, the glass is installed into curtain wall frames, which act as the building’s non-structural covering. Then, the curtain walls are trucked to Boston for installation.

The frames that hold One Dalton’s glass panels are not meant to be seen, unlike in Cobb’s work on the glass-paneled Hancock Tower, where black frames create a scaled geometric look.

“In this case, it’s very different. The continuity of the glass is almost complete,” says Cobb. “The frames are virtually invisible from the ground. You’ll see little aluminum edges, but that’s about it.”

The glass covering One Dalton will also be unusually thick, which helps with wind resistance and lowering light deflection. It also acts as a noise suppressor and insulator, thanks to argon gas inserted between the layers

Image courtesy of Rasky Partners, Inc.

Cobb, who founded his firm Pei Cobb Freed & Partners in 1955 with legendary architect I.M. Pei, worked with architect Roy Barris and Cambridge Seven Associates to design Boston’s newest glass tower. They decided the building’s shape would resemble a “soft triangle,” with three curved faces and three distinct sections meant for public space, hotel rooms, and private residences.

First, there’s the “podium,” which acts as a base. The podium is constructed of clear glass set in Chelmsford granite, and grows outward to meet the street. It contains all of the quasi-public spaces of the hotel and residences in the building, including lobbies, restaurants, and ballrooms.

Then, at the height of the Christian Science Center, the building shifts into its soft triangle shape and becomes more narrow. This section is made up of 20 floors of hotel rooms, before another shift—signified with a use of metal—opens up the building to the top 35 floors of residences.

“[The transition] is eventful but seamless,” says Cobb. “It rather consciously, deliberately occurs just as the tower begins to rise above its immediate neighbors.”

One Dalton’s lower floors will contain 215 rooms for the Four Seasons Hotel, while the private residences will exist on the uppermost floors. (Boston is now one of the few cities that can claim a residential tower managed by the Four Seasons, along with New York, Shanghai, and London.) The 160 residences, which are expected to cost an average of $6 million, will all have fireplaces, and some will boast private balconies. The four-bedroom, five-bathroom penthouse unit is said to be on the market for about $40 million—and if it were to sell for that much, it’d shatter Boston price records.

Image courtesy of Pei Cobb Freed & Partners

Future inhabitants are set to enjoy a slew of upscale amenities, including a private theater, restaurant, salon, health club, spa, and a golf simulation room. There are also laundry services, housekeeping, and a 24-hour valet. The building’s stately amenity spaces have been designed by Thierry Despont, known for his work on the Ritz Paris and the Cartier Mansion on Fifth Avenue in New York.

Richard Friedman of Carpenter & Company, the developer of the property, says the building reaches a level of luxury Boston has never seen. (And he would know—Friedman developed both the Liberty and the Charles hotels.) Having the property designed by a legendary architect is just the icing on the cake.

“He’s 91 years old and he told me the other day ‘I’m in mid-career,’” Friedman says, who likes the building so much, he bought himself a condo on the 49th floor.

“We had a blast with him. He’s been great. He’s fantastic,” Friedman says.

In Cobb’s eyes, the building—with all its bells and whistles—is a success if it exists harmoniously within the context of its surroundings.

“By definition, a building of this size becomes an iconic presence in Boston,” says Cobb. “I believe in place and occasion. That’s what drives our design philosophy. And it’s particularly important, in my view, in Boston, which is a city with so much character and so many different kinds of places in it. So, this building is designed for its place in that city.”

Image courtesy of Rasky Partners, Inc.