The 80-Year-Old Gropius House in Lincoln Is a Modernist Marvel

How Walter Gropius built a Bauhaus dream house in a Boston ’burb.

The family’s original furnishings, including the Sori Yanagi stools by the fireplace, still fill the house. / Photo by Toan Trinh

This year marks the centennial of the Bauhaus, the design school founded by modernist pioneer Walter Gropius in Weimar, Germany, in 1919. But the building that best embodies his philosophy isn’t in Germany; it’s in Boston’s backyard, perched on a hill in bucolic Lincoln, where Gropius House looks much as it did when the architect and his family moved in back in 1938.

Lured by a post at Harvard, Gropius had relocated to Massachusetts in 1937 with his wife, Ise, and daughter, Ati, renting a house in Lincoln while they planned for a home of their own. At the request of a mutual friend, philanthropist Helen Osborne Storrow provided land for and financed the construction of the new abode—a boon for a family that had been forced to abandon assets when they fled Nazi Germany for London in 1934. While Gropius and his partner Marcel Breuer were the official architects, the design was discussed nightly around the dinner table. Ise was the chief landscaper, and 12-year-old Ati offered input, too, requesting her own private entrance. Dad obliged with an outdoor spiral staircase, a curvy counterpoint to the clean-lined exterior that, he later wrote, “proved to be very practical because children could enter there directly without carrying dirt through the house.”

You’ll find that modernist marriage of form and function everywhere. “The vision of Walter Gropius included an almost utopian sense that simple, affordable, aesthetically pleasing, and functional architecture should be the way forward,” says Wendy Hubbard of Historic New England, which now operates Gropius House as a museum. “The materials, in fact, are the aesthetic.” Those materials included novel industrial ones such as sound-absorbent acoustic plaster, glass blocks that helped draw in daylight, and sleek pieces from companies such as Kliegl Bros., whose commercial light fixture showcased the dining room table.

Despite the home’s modern look, traditional New England design inspired the architect, who wrote, “The old white-painted Colonial houses, unpretentious and genuine in plan and appearance, won my affection.” / Photo courtesy of Historic New England

But the Gropiuses didn’t just want to bring the Bauhaus to Boston; they wanted to synthesize its principles with what they found in New England. To that end, the home’s modern rectilinear structure rises from a familiar fieldstone foundation, and in the entryway, you’re greeted by clapboard—a staple of the classic Colonials Gropius admired. But he used the material in a new way, arranging it vertically in the interior, not horizontally outside. “This mix of tradition and nontradition, of commercially available materials used in a domestic setting—all of that feels contemporary,” Hubbard says.

Above all, the couple thought a modern New England house should exist in harmony with its natural surroundings. They selected Concord grapevines and other indigenous plants for the grounds and scaled the structure at a modest 2,300 square feet. It feels larger thanks to the outsize windows. “There is nothing,” Gropius wrote, “like watching a blizzard through twelve-foot-long glass panes while sitting at the dinner table.” These, too, were practical, positioned for passive heating; on bright winter days, the home’s temperature could hit 70 degrees even if the family turned off the heat. In summer, the cantilevered roof functioned as a brise-soleil, blocking high-angle sun, while the screened-in porch became a breezy second living room.

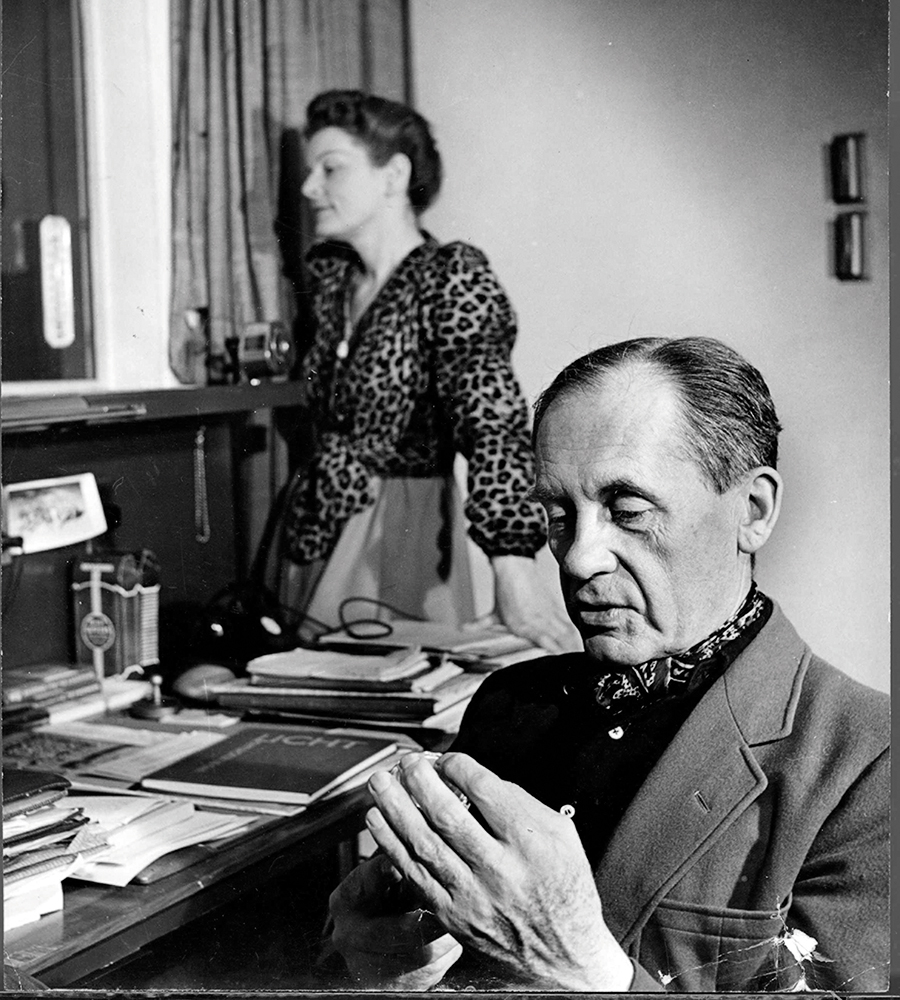

Ise and Walter Gropius worked side by side at their Bauhaus-designed double desk in the study. / Photo courtesy of Historic New England

Of course, every room feels like one designed for living, an effect heightened by the fact that the home’s contents have been largely left intact. Art by famous friends Joan Miró and Josef Albers hangs on the walls. Books line the shelves; coats wait in the closet. And the décor includes the biggest collection of Bauhaus furniture outside Germany, plus later additions that became modernist icons, such as an Eero Saarinen “Womb” chair—a 1953 birthday gift to Gropius that’s still produced today.

Gropius’s ideas have stood the test of time, too. “How they treated their landscape, how they heated and cooled their house, how he designed a modest dwelling—all of that resonates today,” Hubbard says. Indeed, one testament to his legacy is how much we take his insights for granted. A century after the Bauhaus was founded—eight decades after the blueprints for Gropius House were drawn—we don’t think of his ideas as belonging to a particular period; we think of them as good design.