An Oral History of the Last Real Bar on Martha’s Vineyard

Key West has Sloppy Joe’s. Havana has El Floridita. And our very own Oak Bluffs has the Ritz Café. After 75 years, it’s time to celebrate the best little dive in paradise.

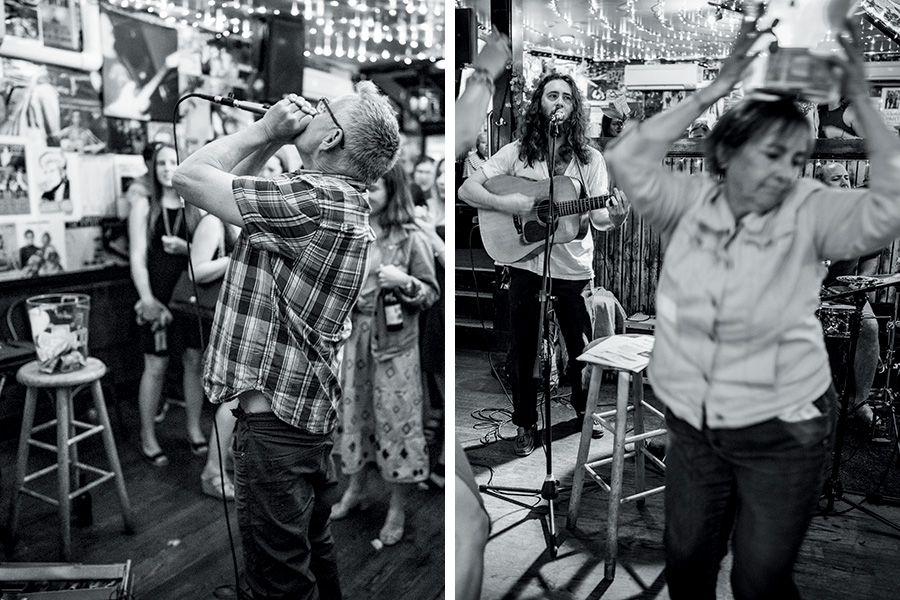

Photos by Jeremy Driesen

Exhume an early-20th-century native of Martha’s Vineyard today, and they’d hardly recognize their island. The Gay Head Cliffs, the great ponds, and the beaches would still look familiar, but almost everything else is different—enlarged, renamed, upgraded, upscaled, or simply wiped away. Summer crowds are bigger than ever these days, traffic jams clog the quaint streets, and August vacation season verges on being a blood sport. Among the last remaining holdouts is the Ritz Café, which—along with the cliffs, the beaches, and the ponds—has held the line. A modest watering hole that islanders depend on after the day’s work is done and the summer crowds have evacuated to the mainland, the institution, which celebrates its 75th anniversary this year, has acquired the patina of legend.

If it’s a dive, it’s one that argues there’s more to the designation than peeling paint and a well-worn bar. Located next to the shinier, chicer bars that now line Circuit Avenue in Oak Bluffs, the rough exterior might scare off the faint of heart. And while the aura is arguably friendly, it’s also a bit reckless, hinting at a long history of spirited delights: It wasn’t unheard of, for instance, for regulars to throw a fake wedding at a moment’s notice. While other parts of the island have been spruced up and civilized, the atmosphere inside the barroom harkens back to the impromptu, unsanctioned revels put on by clannish islanders throughout the 1970s and ’80s—the horse races at John and Kappy Hall’s farm, the demolition derby at Hughie Taylor’s Gay Head (now Aquinnah) field, iceboating on a Sunday morning at Squibnocket Pond—capturing a timeless spirit.

A narrow, ground-floor, walk-in space built in 1930, the establishment debuted as the Ritz Café in 1944, Richard L. Pease proprietor. The bar was to the right of the door, featuring jars of 50-cent pickled eggs, with a few square tables, four chairs each, to the left. In an adjoining space up three steps, called Topside, there were pool tables. The place had a decidedly fishboat-green motif, with a design that emphasized the predictable need for periodic rapid rehab after a particularly boisterous evening.

In 1967, when Arthur “Lanky” Pachico bought the bar, fewer than 7,000 souls lived on Martha’s Vineyard year round and only a handful of ferries carried people and freight to and from the mainland at Woods Hole. At the time, only two towns—Edgartown, the county seat, and Oak Bluffs—allowed the sale of alcohol. On any bitter, wind-harried winter evening, the lights at the Ritz extended the only welcome to be found, from one end of cheerless Circuit Avenue to the other.

Over the years, the Ritz proved a reliable refuge for characters chock-full of personality and grit. In the days when island tradesmen, shopkeepers, and workers of all sorts were laid off in the fall and rehired in the spring, the doors opened early on Tuesday mornings for folks signing up for the weekly unemployment-check distribution. It was the chosen hangout for a certain breed of islander, like “Johnny Seaview,” born Oliver Perry, a wiry, Stetson-wearing former horse jockey and onetime bartender who hitchhiked up- and down-island carrying a chainsaw and other implements for the dismemberment of trees and shrubs. When Lanky’s stepdaughter, Janet King, took over the bar after he died in 1986, she transformed it into a swinging little dance hall where passersby might hear the driving bass and blues harmonica of Johnny Hoy and the Bluefish booming from inside as a chattering crowd hung near the entrance. And today, under the stewardship of Larkin Stallings, a Houston transplant who bought the Ritz in 2014, the island’s most authentic bar remains a vital outpost—a living, rocking legend worth celebrating.

Photos by Jeremy Driesen

Janet King, co-owner, 1986 to 2014: From the age of 12 on, I’d help my mother clean and open the bar. I mean, she didn’t constantly have me doing it, but I would help my mother with the cleaning. Then, a few years later, I worked as a bartender. And I started working with my stepdad when I returned home after a few years in Boston. I took bartender shifts in the summer, and I was the bouncer and ID checker.

Jeremy Berlin, longtime piano player with Johnny Hoy and the Bluefish: This was the place for the longest time. All these other places you see on the island now were really Johnny-come-latelies. They wanted to have what the Ritz had.

Johnny Hoy, frontman and blues harp player for Johnny Hoy and the Bluefish: They had a bit of live music back then. [Laughs.] Lanky liked music.

King: It was 1986 when my stepdad passed away and I stepped in. I just took over his job. I mean, somebody had to do it. But it wasn’t just mine, because my mother owned it. When she passed away, it went to all four kids, and the four kids weren’t all on the same page with everything. And I needed all of their help. I couldn’t do it by myself.

Berlin: The family ran it on tradition and dysfunction and love and hate and sisterly—what’s the word for the opposite of fratricide, for siblings who want to kill each other?

Hoy: Janet was opinionated, and once she made up her mind, man, there was no going back. She had a will of stone, you know. She could be wishy-washy at first, but once she fucking decided something, that was it.

Berlin: Janet was also happy to say at first that she had no idea what she was doing—because she really didn’t. She did not know how to run a business.

King: I just stepped in and started to do what I knew that my stepdad did every day. I did the same thing. It was just the regular, same old people in the morning and afternoon. You had to put some people out, you had to turn some people off. So I did, but not so many back then. I did have some fights.

Hoy: You didn’t want to mess with Janet. When you’re very nice it’s fine, but if she got pissed at you she could put a big man down, just boom. She was known in high school for a while for being a brawler, if she had something with anybody that pissed her off. I mean, she’d just go for the jugular.

Berlin: Every spring, you see a brawl outside the Ritz. One even happened last weekend.

Hoy: I wrote a song for Janet and sometimes sang it to her in the bar. It goes: Hey, Janet, want to dance?/She’s the queen of the Ritz./She’s the judge and the jury, with a smile on her lips./But when you walk through that door, boy you best behave yourself right./’Cause they got a fate worse than death down there:/She could bar you for life.

King: I’ve had a few physical fights, not tons of them. One was with Johnny Seaview.

Hoy: Johnny Seaview was buddies with Lanky, Janet’s stepfather. And I mean, that was back when this was a fishing town.

Coop deVille executive chef Lawrence Jackson, who worked at the Ritz from 1998 to 2014: I used to hang out with Johnny Seaview. He was kind of a pain in the butt, but he still was a really good guy. He used to come and bring all the female bartenders flowers and candies and stuff. Everybody really liked him, even Janet. She did shut Johnny off one time and told him he had to leave, but he wouldn’t go, and they ended up wrestling. But with some help, he left.

King: When it did get busier and crazier later on, I had a staff to help with the unruly people.

Hoy: Janet is a music lover. She loves a singer. She loves anybody that can really carry a tune. She likes what she likes, and she knows that she likes soul. She likes a singer that’s got it.

King: One time there were a couple of people playing music, a girl and two guys from California, in the little alleyway that leads to the nearby campgrounds. It was a rainy day in the summertime. They were playing music and the girl was singing. I stopped to talk to them, and she said they were stuck here. They didn’t have a place, there were no boats, it was raining, and they couldn’t get back to the mainland. I said, “Oh, I have an apartment above the Ritz. If you want to sleep in the apartment and play at the Ritz that night for the apartment, I’d love to have you.” And that’s what they did, and it was fabulous.

Berlin: The apartment above the bar made this place very special. We had the local bands, but we also had regional bands and bands from far away that would come in and stay here. We’d done this in other places, where you get sort of a subsidized vacation—a place to stay, a gig—and it’s awesome. You go to the beach during the day, and for a band to come to the Vineyard and have that setup and then be able to go downstairs and play there, it was a scene. And the after-parties were legendary. Susan Tedeschi cut her teeth here.

King: Over the years, I did see some acts flop. I once had a band that came in with so much equipment that there was no room for people, and I had to go up on stage and say there’s no room for anybody to dance. It’s a pretty big room, but it’s not that big.

Hoy: Janet would go to bat for someone she liked and put them up in the back room. You know, she brought in the bands. She made it happen.

King: The floors were always bouncing. It used to get so crazy in there.

Jackson: I was working back when Janet used to “marry” people at the bar. It wasn’t a real marriage. It just was a fake marriage. Janet’s sister once got “married” to somebody, and the person was so wasted he actually thought he was really married. We had to tell him the next day, “It’s only fake, man!”

Hoy: There were a bunch of skunks living under the floor. Did Janet tell you that? It was like a family of skunks under the floor of the upstairs bar. If the floor started bouncing—even when they were hibernating in the winter—you’d make them nervous and they’d let it go. I mean the place—if was a hot night—the floor would start to move, and then the next thing it was like, gah! It would reek. As a band, you really knew you had it going when the skunks let it go.

King: After we renovated the kitchen, we put in oak floors. Right after we finished the renovation, one of the bartenders told me a musician was nailing his drums to my brand-new oak floors. I went out there to ask him what he was doing, and he said that’s what musicians do. They don’t want the drums to move. So I didn’t stop him.

Hoy: It was amazing to have a hometown bar that was as good as it was. I mean, this place could have gone any which way after Janet. It could have been a T-shirt shop/pizza place, you know?

King: I do miss the place. But I don’t regret selling it because I was tired, and I knew it needed somebody else to get in there and run it right and get it going again.

Photos by Jeremy Driesen

Larkin Stallings, owner since 2014 along with his wife, Jacqueline: Originally I’m from northern California, but I moved to Texas in ’78 to go to college, stayed, got married, and raised four kids. My wife, when I first met her 30 years ago, said someday we’ll live on Martha’s Vineyard. I was like, “Where the fuck?” because she had never even been here before. She’s from south Texas. She just had a dream, and we started coming for summer vacations. Then we bought a house here, right at the top of the market, so we could never sell it.

Berlin: It’s amazing to think how freakin’ lucky we are that we made the transition from Janet to Larkin.

Stallings: I just saw the sale sign on the door one day. I look back on that day sometimes with great fondness and a great sense of, What the fuck was I thinking? But you know, most of the businesses, most of the restaurants and the bars on Martha’s Vineyard have gone through lots of owners over not so many years. This place, though, had gone through very few owners over a long, long period of time.

King: Closing the sale turned into a whole big fiasco. I had a real estate agent who had this buyer who said he wanted the place and signed an agreement and supposedly had put down a payment. So to celebrate we had a big closing party, but the sale didn’t go through. So then all of a sudden it was going to happen again, so we had another closing party, but it fell through again. We had three closing parties that everybody came to and we had a blast at them all before the final sale.

Hoy: Larkin got the sense of the place right away. He walked in, took it in, and he just got it. And then he tweaked it. He wasn’t afraid to put his mark on it. At the same time, Larkin has really stuck up for us old guys, but there’s a bunch of young turks breathing down our necks.

King: Young singers and performers have approached Johnny Hoy and Jeremy Berlin over the years, and they take these people on and sort of tutor them. I think Johnny helped quite a few people by letting them play with his band here.

Delanie Pickering, blues guitarist and singer for the Bluefish: They found out I played guitar, and then they’d be like, Come up and sing a song. So I’d sing and play and now I’m in the band.

Hoy: Delanie’s got natural talent.

Pickering: I’ve been playing music since I was 16, and we had a piano in the house. Then I started bombing around all over the East Coast, and then I stopped playing and I moved here randomly. I ran out of money and I was living in my van and I used to drink in the bar. The first night I got here, I just stumbled into the Ritz and quickly learned it’s the bar with music every night, so you can go back every night.

Hoy: The problem with playing the home bar is that everybody’s heard all your stuff. So you’re trying to dig deep into your 300 songs and dust off something they haven’t heard. And some of them are going to fall flat on their face, and it’s dangerous, but that’s what we do. We do take a lot of chances in here and the crowds are very forgiving. I think the chemistry and the dynamic between the crowd and the band makes it the best home bar ever.

Stallings: What’s the essence of this place? I think it’s music. I think it’s comfortable first, and you can get some music, and it’s welcoming. We have a really good, friendly staff that actually gives a crap about the island and the people who come in, including our summer residents, our summer visitors. They count as much as anyone.

Hoy: The old people drink water now, you know. If you’re going to survive in the bar business, you got to have youth in here.

Stallings: It’s a place where you can come in no matter who you are, sit down, and you may just be sitting next to an actual commercial fisherman, a working man. Or you may be sitting next to Larry David, and it just works. We have no pretension about who we are. We don’t pretend that we’re fancy.