The Curious Case of Clearway Street

The alleged displacement of nearly 100 residents from a refuge of affordable housing in one of Boston’s most intensely gentrified neighborhoods has revealed how the city’s colleges and universities can exacerbate its housing crisis—and there’s nothing stopping it from happening again.

In the summer of 2014, Berklee College of Music approached the city to see how receptive it would be to the college amending its Institutional Master Plan (IMP) in order to master lease a block of apartments on Clearway Street, located off Massachusetts Avenue and owned by the Christian Science Church. Berklee students wanted to live on-campus, and school officials were scrambling to accommodate them in time for the new semester.

Anticipating little pushback, the Boston Redevelopment Authority proposed issuing a temporary certificate of occupancy, on the condition that the amendment would likely be approved. But when some Fenway residents responded negatively, the BRA decided better of it.

“Although many people were in fact supportive of this concept, others were not, and the city has therefore determined that it will not support this master lease for the coming academic year,” wrote Gerald Autler, senior project manager at the BRA, in an August 14, 2014 email to community members. “If the parties involved are interested in proposing such an arrangement for subsequent academic years, we will notify you of a public process whereby the proposal can be discussed and shaped with more time.”

Three days later, Berklee director of housing Marguerite Sharkey referred an incoming student to Hunneman Management and Development Company, which manages the Church’s apartments on Clearway Street, in an email provided to Boston. Sharkey says Berklee “facilitated arrangements” with Hunneman to address its overflow of students in need of housing. She and her colleagues even toured the apartments, and were “impressed with their care and condition.”

“Hunneman has already reserved an apartment assignment for you. Berklee provided them with the list of affected residents, and they have made assignments to apartments in much the same manner as Berklee would have done,” Sharkey wrote. The arrangement was part of a pilot program by Hunneman aimed at college students. Each apartment would be outfitted with furniture “similar to what is provided in college residence halls.”

Around this time, the Fenway Community Development Corporation (FCDC) says longtime tenants of Clearway Street’s two-bedroom apartments learned that renewal offers would not be extended, while month-to-month tenants received 30-day eviction notices. One of the street’s residents, who shared a $1,600-a-month, one-bedroom apartment with her husband, told the FCDC she had watched movers hauling “uniform-looking dorm-style furniture” into the apartments.

“Once existing tenants had vacated the impacted apartments upwards of four Berklee students were moved into these two-bedroom units,” wrote FCDC executive director Leah Camhi and president Louvere Walker in an August 21, 2015 letter to BRA director Brian Golden. “Berklee actively facilitated placement of Berklee students in Clearway units.”

Camhi and Walker said that based on what they’ve learned in interviews with residents, those two-bedroom units are going to the students at a rate of $900 a month each, or $3600 a unit.

Boston City Councilor Josh Zakim, whose district includes Clearway Street, wrote Golden too. Citing 2013 voter lists, Zakim concluded, “it now appears that Berklee has disregarded the IMP process and is housing many of its students on Clearway Street. I urge the BRA to look into this possible violation of the IMP and take appropriate remedial action.”

“It certainly didn’t occur to me. It didn’t occur to anybody else [that the case was not closed after that initial email],” Autler says. “We understood that [Berklee] had a housing problem to solve, and that one way or another, those students were going to find housing. But I was unaware of the fact that the students had moved, as a bloc, into those apartments contracting directly with Hunneman, until this summer.”

The FCDC requested that any sort of master lease between Berklee and the Church be terminated as of August 2016; that Berklee and the Church would neither extend renewal offers to Berklee students nor ink any new lease agreements with them; and that Berklee and the Church and its agents would no longer market the Clearway Street units “in a manner that targets or otherwise solicits Berklee students.”

But in his and Inspectional Services Department Commissioner William Christopher’s response to the FCDC, Golden wrote that the BRA did not believe that Berklee violated the terms of its IMP. Since Berklee referred students to sign individual leases with Hunneman instead of entering into a master lease, there was no violation.

“We understand that you find the arrangement between Berklee and Hunneman Management and Development/the Christian Science Church problematic, even though we do not agree that it constitutes a legal violation,” Golden and Christopher wrote.

“We agreed that this is a situation that is concerning, because it shows that colleges and universities can have an impact on the local housing market on a large scale, even when they don’t enter into formal master leases with the private property market,” Autler says.

Christian Science Church real estate manager Jack Train says there is no written agreement in their records between Berklee and the Church or its property manager outlining the referral of the school’s students to the Clearway Street apartments. He also says the Church was “unaware of any special provision for Berklee students until well after the fact.”

“However, I was told last year in October by the property manager that he had filled approximately 20 two-bedroom units with Berklee students,” Train says. “Upon asking whether there was any displacement of existing tenants I was told that only a few units were made available by non-renewal due to problems with the tenants of those units and that none had been a tenant for over five years. Subsequent research by my department suggests that as many as seven units were not renewed.”

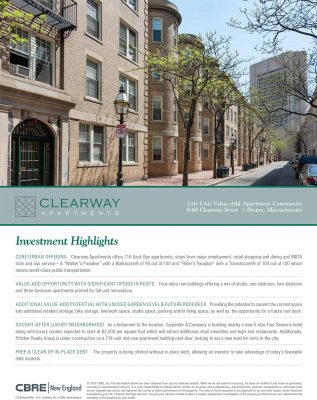

As detailed in an Adrian Walker column from September, the Church wants out of the real estate game. Only stoking residents fears of displacement was a brochure printed by real estate firm CBRE New England—retained by the Church—advertising the 116 units on Clearway Street. The flier boasts the “value-add opportunity with significant upside in rents” located in a “sought-after luxury neighborhood” that’s “looking to set a new level for rents in the city.” There’s even an opportunity for a future roof deck.

In response, the FCDC organized a “funeral for the community” earlier this month. More than 50 Clearway Street residents, joined by housing advocates from the Chinese Progressive Association, Boston Homeless Solidarity Committee, Right to the City Boston, and the Boston Tenant Coalition marched in the drizzling rain from the Church’s Mapparium on Mass. Ave. to Berklee’s administrative building on the corner of Boylston and Hemenway Streets.

It doesn’t get better than this! #ClearwayMarch

Posted by Fenway Community Development Corporation on Wednesday, December 2, 2015

The next day, the Berklee community received an email from Bill Whitney, vice president of real estate, who called the FCDC’s characterization of the situation “simply not true.”

“[The management company] advised us that none of the Clearway Street residents would be displaced as a result of Berklee students moving into those apartments,” Whitney wrote. “It may well be that some renters in the Clearway apartments were not invited to renew their leases by the Church’s property manager, but that was entirely the manager and/or Church’s decision.”

(A spokesperson for Berklee declined comment for this story beyond Whitney’s email.)

Autler says going forward, he’d like to see more communication between the agency and city’s schools in order to allow for more public input and to prevent episodes like Clearway Street. Though he admits it’s unclear how the BRA would be able to regulate this sort of workaround in the future, especially without any regulatory authority, Autler doubts it will become a widespread practice.

“We’re in ongoing talks with all of our colleges and universities on a number of issues related to student housing,” he says. “As we proceed with those, we’re making it clear that this is something that we don’t want them to do, at least without giving us a heads-up because we want a chance to assess.”

In the meantime, Councilor Zakim is still unsatisfied.

“I continue to believe that Berklee violated its IMP—if not the letter than certainly the spirit of it,” he says. “Regardless, such an expansive decision should always involve a community process.”